Oumar Bah’s Bronx-based clothing boutique, O Fresh, has been putting New Yorkers on to the freshest streetwear trends since the days when French Montana was hand-delivering Cocaine City DVDs for Bah to stock. You won’t find any mixtapes in O Fresh today, but you’ll still find plenty of garments that reflect current style trends in hip-hop—from Hellstar hoodies to newly released Avirex leather jackets.

However, there’s only one label that Bah credits as the most integral to his store’s success—so much so that O Fresh has an entire section dedicated to it. Walk inside his boutique and you can’t miss the six-foot long glass case, furnished wood shelves, and mirrored displays full of B.B. Simon belts in every color and style imaginable.

“I'm not selling 10 or 100 belts a day like I did 15 years ago, but I still manage to sell one to three a day,” says Bah as he unravels a “fully loaded” B.B. Simon belt flooded with Swarovski crystals that retails for $600. “I still sell them because they're stable. It’s not a trend. It's at the same level as a Louis Vuitton or Gucci belt. The market might slow down, but it will always go back up.”

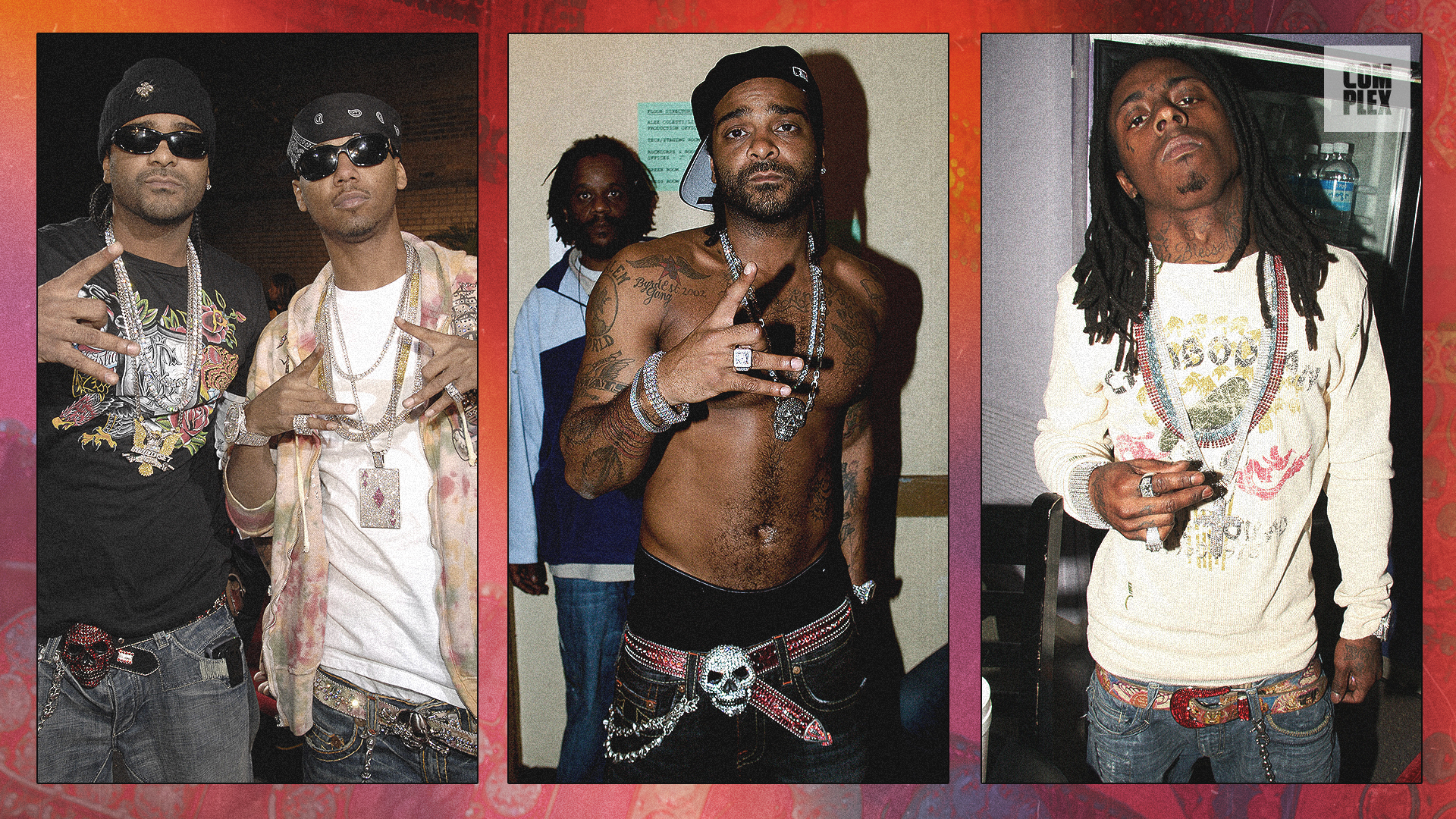

Bah positioning B.B. Simon next to luxury brands isn’t a hot take. Within the ever-evolving world of hip-hop style, B.B. Simon belts have held a grip on rappers’ waists for decades. Originally popularized by New York City rappers like Max B and Jim Jones in the aughts, these colorfully iced-out belts with gigantic buckles are still co-signed by major hip-hop artists today. Whether it’s Doja Cat, Ice Spice, Travis Scott, or Smino, wearing a B.B. Simon belt feels like an unspoken rite of passage for any rapper ascending to fame.

But B.B. Simon’s success story isn’t just due to the hip-hop artists who co-sign it. The brand’s rise is also the story of immigrant entrepreneurship—from the Iranian who founded the brand in Los Angeles, to Oumar Bah, who moved from Germany to NYC with dreams of opening a store dedicated to hip-hop culture. Both men tapped into their creativity to help turn an extravagant accessory into a hip-hop staple.

“New York City was always the number one city that recognized B.B. Simon. It's not even comparable to what we have in L.A. today,” says B.B. Simon’s 70-year-old founder Simon Tavassoli. (The brand’s moniker is an abbreviation of Belts By Simon.) “The way Oumar was buying my belts at trade shows, even calling me and flying to meet me in California or Las Vegas, always surprised me. I thought he was sending them or exporting them elsewhere. But no, he was really selling nearly everything in New York. To this day, it's still a very important city for me.”

An Asylum Seeker Turned Fashion Designer

Even before starting B.B. Simon in 1986, Tavassoli remembers having an entrepreneurial spirit. By the time he turned 18, he was already a successful customs broker in his home country of Iran, owning a shipping business that hired several employees before he could even grow a mustache. But in 1979, the Iranian Revolution killed all shipments to and from Iran, forcing Tavassoli to pivot to the fashion business in his early 20s. Operating a high-end clothing boutique in Tehran, Tavassoli traveled frequently to European fashion capitals like Milan with his friends to bring back suitcases filled with $5,000 Italian suits to resell.

“I was bringing these goods in through planes, trains, buses, and cars. I literally drove through Turkey, Bulgaria, and even Yugoslavia when it was still one country,” says Tavassoli. “I did that for two or three years and made good money.”

But that money train stopped in 1980 with the start of the Iraq-Iran war. No longer able to freely travel out of Iran, Tavassoli closed his boutique and opened a high-end supermarket, knowing that food-related businesses would always be needed. Unfortunately, his business nosedived as the war intensified. Eventually, the government took over his supermarket and rationed everything from chicken to cigarettes with coupons, decimating his profit margins. Frustrated with the Iranian government—and even persecuted by them—Tavassoli decided he had to leave the country.

“The reason I came to America was because I had to run away from Iran. You can't grow in that country. As soon as you talk about what you're actually thinking, you're in trouble,” says Tavassoli. “The Iranian government arrested me and put me in a prison cell for 15 days because I was speaking out about what was going on too much. After I got out, I just didn't feel safe and comfortable in Iran anymore.”

Tavassoli moved to America in 1986 as a 32-year-old asylum seeker. He got his start making traditional 30-millimeter belts at his uncle’s factory in L.A.. He quickly picked up the basics in five months and began creating his own ladies’ belts with buckles he designed. That spark led him to open his own business, Belts By Simon, in a 300-square foot office that he paid $500 a month for on 7th Street in downtown L.A.. His first stockists were local womenswear boutiques in California. Business grew quickly.

"It’s not a trend. It's at the same level as a Louis Vuitton or Gucci belt." -Oumar Bah

By 1988, Tavassoli was working in a larger office in Orange County, designing women’s belts and handbags inspired by the same high-end European brands he used to sell in Tehran. For the next 10 years, he worked the womenswear trade show circuit, presenting his styles at convention centers and showrooms across the country.

Momentum was starting to build, but to truly break through, every brand needs a signature product. For Tavassoli and B.B. Simon, that innovative item was a belt decorated with Swarovski crystals, which he debuted in the early 2000s. Millions of dollars in sales later, Tavassoli still designs these belts like fine jewelry. Each one is handcrafted in the United States with Italian leather, gigantic belt buckles from Taiwan, and Swarovski crystals from Austria. Tavassoli says he keeps a “couple million dollars” worth of materials, including 48 different colors of Swarovski crystals in 10 different sizes, at his factory in Irvine, California. Each B.B. Simon belt takes three to four hours to make.

“We could fit 280 stones on the belt itself and put between 300 to 500 on the buckles in one style. Other styles will have 150 stones on the buckle and 285 stones on the belt. Some more, some less, it all depends,” shares Tavassoli, whose factory today includes over 85 employees that have made as many as 2,500 belts a month in recent years. “Everything is handmade and the people who work here are doing each belt and buckle by hand. It's not as easy as people think.”

Tavassoli says the belt’s exaggerated buckles first resonated with fans of cowboy couture after Madonna wore one in the music video for her 2000 country-pop song “Don’t Tell Me.” The Midwest market became huge for B.B. Simon. Cavender's, a retailer centered on Western fashion, stocked the belts in over 65 stores nationwide. Each order brought in as much as $1 million for the brand during the early 2000s.

But the belt’s ostentatious bling had appeal beyond cowboys, which drew a New York City-based store owner to reach out to Tavassoli and see if he could sell his wares to a different type of clientele. It was an intuition that helped turn B.B. Simon into a business that would make $15 million in gross sales by 2009.

How B.B. Simon Belts Took Over New York

Whether it was a leather Pelle Pelle jacket or a gray-under brim New Era fitted, Bah’s been selling iconic items that speak to hip-hop fashion trends since immigrating to New York City from Germany in 2002. The 44-year-old shop owner grew up obsessing over hip-hop culture and style, so much so that he relocated to its birthplace to pursue his dream of opening a business dedicated to it.

“I grew up going to stores like G-Star in Hamburg and fashion had always been on my mind, but Germany wasn’t New York,” says Bah. “The opportunity to open a store in New York City was different. So I started from the bottom here and kept going.”

Bah began his career airbrushing graphic T-shirts in Harlem. However, spending two to three hours on a single T-shirt to only make a couple hundred dollars at the end of the day wasn’t worth it. He moved on to selling gold accessories, mixtapes, and hip-hop DVDs at a stall inside his sister’s Harlem fitted-cap boutique, Cap USA. He went on to work at Genesis, a bygone streetwear boutique in Midtown Manhattan. At the time, Genesis was the place for New York rappers to go buy pieces like Jeff Hamilton jackets. It was also where Bah first saw B.B. Simon’s style hitting with his clients—at least the knockoff version. Genesis stocked a $20 B.B. Simon dupe that sold well.

“You could tell the difference. It was like having fake and real diamonds. When you wore a B.B. Simon at night, that shit shined,” remembers Bah. “All the other lookalikes didn't do that, but when I started selling those, it went crazy for like three months. I said to myself, ‘Wait a minute, nah, this right here, I got to get into this because this is crazy.’”

Bah did his research and found B.B. Simon’s showroom on 38th Street and Sixth Avenue. Upon learning that real B.B. Simon belts were flooded with Swarovski crystals to make them bling (and cost nearly $400 a piece) he knew he had to bring them to Genesis—and eventually, O Fresh, which he opened in 2005. Although he had no money, he pitched Tavassoli a proposal.

“I went directly to Simon and asked him to just give me a chance, give me a couple pieces to try this out,” says Bah. “We started with 50 belts, each cost $400 to $500. Within a week, I called him back and said I had his money, I needed more belts, and I needed to have the opportunity to let clients make customs.”

Bah became B.B. Simon’s first distributor in New York and likely sold most of the B.B. belts seen on New York rappers in the 2000s.

“Max B and French Montana invited me to bring the belts to a show in Connecticut once. I grabbed like 25 belts, put them in my bookbag, and I went with them,” remembers Bah. “I was by the stage selling B.B. belts like it was nothing because Max had it on.''

Between 2005 and 2014, Bah estimates he sold around 30 to 40 B.B. Simon belts a day. He remembers how customers used to even line up at O Fresh's original location on Fordham Road in the Bronx to buy belts like they were coveted Jordans on a release day.

“It’s funny because Simon wasn’t even focused on belts at the time, he was selling custom furniture, like $250,000 Swarovski-flooded pianos, to wealthy families in Dubai,” says Bah. “But when we started seeing how those belts moved, it was a movie. If you didn't have a B.B. at that time, your outfit just wasn't lit. B.B. killed MCM, LV, and Gucci.”

Although everyone from Travis Scott to Katt Williams have purchased B.B. Simon belts off Bah, he credits Jim Jones and Max B for being the first celebs to bring it to the forefront. Indeed, Jones tells Complex that he first discovered B.B. Simon belts at Genesis, which was only a 10-minute cab ride from Harlem, and fell in love with them because it aligned with the rockstar persona he was building for himself as an artist at the time. He credits his style in the 2000s to several different inspirations. He brought back the James Dean-esque motorcycle jackets he loved as a teenager. His partner Chrissy Lampkin put him on to brands like Chrome Hearts. And because he lost his wallet so often, his friend gifted him a Harley Davidson wallet chain. But the B.B. Simon belts were the pièce de résistance of his outfits.

"If you didn't have a B.B. at that time, your outfit just wasn't lit. B.B. killed MCM, LV, and Gucci.” -Oumar Bah

“When I first got them, Genesis was the only store that had them in New York City. That's why it was so exclusive,” remembers Jones. “That's why I was really able to get it off the way I did, because no one really knew where they were at for some time. I remember Weezy [Lil Wayne] started dressing in the vein of how we were dressing. He began asking where we got certain things and eventually asked us about what kind of belts we were wearing. He took it to the next level and actually went to the B.B. Simon factory in L.A.”

Tavassoli acknowledges how foundational rappers like Jones, Wayne, and Juelz Santana were for the brand’s growth. He remembers when they all visited his factory in 2008, with each spending $54,000 on 180 belts for themselves, friends, and family. At its peak in the late 2000s, Tavassoli says B.B. Simon manufactured as many as 15,000 belts a month and the label brought in nearly $15 million in gross sales by decade’s end. But after his belts blew up, counterfeits flooded the market; gross sales were down to $2.5 million in 2011.

“By 2009, Chinese bootleggers were already making replicas and copying everything. That damaged my business for a while,” says Tavassoli. “They made belts with junk that was worth a fifth of the price. But within the last couple of years, the hip-hop community has picked up on the belts again.”

B.B Simon’s Everlasting Appeal

Hip-hop’s love for B.B. Simon has kept Tavassoli’s label relevant. It’s why Bah’s O Fresh remains a loyal stockist for the brand, in case the next hot New York rapper steps into his store looking for an attention-getting accessory. He saw it happen in 2017, when Tekashi 6ix9ine stopped by to pick up 18 different B.B. belts to shoot the music video for “Tati.” That song hyped up B.B. Simon that year, thanks to a viral hook about styling them with Robin’s jeans—a bar sampled from a 2012 New York City YouTube freestyle by the Bronx rapper Yoppy. Bah’s faith in the belts paid off. He was the only stockist selling B.B. Simon belts in New York City at the time. In recent years, he’s sold them to New York drill rappers like Kay Flock.

“To me, it's a piece that everybody loves but not everyone can get because of the money,” says Bah. “You either have money or are on the level of becoming a famous artist. Right now, the people who come in and buy it are those who really fuck with it.”

Tavassoli’s brand was struggling throughout the 2010s up until 6ix9ine re-introduced the brand to a new generation of hip-hop fans. In recent years, plenty of mainstream rappers outside of New York have also kept B.B. Simon’s momentum going. Post Malone commissioned Tavassoli to craft a custom belt to match his Grammys red carpet look in 2019. Jack Harlow’s 2020 hit single “What’s Poppin” surged B.B. Simon’s popularity again that year due to a catchy bar about girls unfastening his B.B. belt. The Harlow co-sign did wonders for Tavassoli, who serendipitously opened a flagship in Melrose in August 2020.

“Within two months of opening, we sold over 4,000 belts in-store and made $1.5 million through in-store revenue,” shares Tavassoli. “We got six times more orders online that year.”

When Ice Spice donned two B.B. Simon belts in her music video for “In Ha Mood” last year, Tavassoli saw interest in B.B. Simon belts spike up again.

“It's interesting because I always see who visits our website on the backend. When one of these rappers wears it in a music video, a concert, an Instagram post, or something, I just see the visitors jump,” says Tavassoli. “We usually have 17,000 to 18,000 visitors to our site daily. If l look at the numbers, it’s mostly traffic from the East Coast, with New York almost always being number one.”

B.B. Simon’s chokehold on New York, and streetwear at large, has even led to two collaborations with Supreme. For Supreme’s Spring/Summer 2020 collection, B.B. Simon produced 500 belts that have resold for over $1,000 on StockX. Supreme’s Spring/Summer 2022 line also included B.B. Simon dog collars with leashes, rhinestone-studded denim, and a rhinestone-embellished puffer that was donned by ASAP Rocky. Tavassoli has also been expanding B.B. Simon’s apparel offerings by releasing items such as backpacks and matching sweatsuits. Bah says New Yorkers have also been receptive to buying B.B. Simon products outside of belts, sharing he’s sold B.B. Simon sweatsuits for $700. Younger clothing boutique owners in New York City have also found success stocking B.B. Simon’s latest wares.

“While their primary product offerings are still belts, accessories like chokers and bracelets are also flying off our shelves,” shares Matt Choon, the 27 year-old owner of the Lower East Side streetwear boutique Bowery Showroom. “Bringing on B.B. Simon was a huge moment for us as they are one of the legacy brands that we grew up surrounded by. With the resurgence of the Y2K movement, there was a unique opportunity to provide the newer generation an authentic opportunity to engage directly with the brand.”

A younger perspective is also informing the direction of Tavassoli’s label today. A part of the label's current success is attributable to its 28-year-old creative director Jay Evans, who has been helping Tavassoli since B.B. Simon’s resurgence in 2018. Evans is responsible for connecting the brand to younger artists, growing the label’s social media presence, overseeing its flagship on Melrose, and even designing some of the label's newer offerings.

“I had seen the belts on Dipset and Lil Wayne in the past. But when it came back in the social media age, B.B. Simon actually wasn't even on Instagram,” says Evans. “Honestly, no one around me knew what these belts were until I started coming around with like 15 to 20 on my neck. I started hanging out at music studios and began selling belts directly to artists.”

Tavassoli admits that even though he’s still attracting new fans, the resurgent hype for B.B. Simon belts in recent years likely hit its crest in 2023. While he declines to specify how his brand performed financially last year, he said it was the first year his revenue went down since 2020. His plan to address competitors and counterfeiters is by designing new belt buckles for his line that leans into the brand’s trademarked logos. However, Tavassoli says this year will likely be his last working as the founder of his company.

“By the end of this year, I'm going to start looking around to see if I could sell the business,” shares Tavassoli. “I still envision myself being on the side to help the brand. But, I'm tired. I’ve been working 52 years. It's just too much.”

Retirement plans aside, Tavassoli still views his brand as untouchable and isn’t worried about the future. Besides, his OG supporters know that when it comes to hip-hop style, the freshest pieces never have an expiration date.

“I mean hip-hop has always been nostalgic of something that's fly. If something was fly that you loved as a kid, that you couldn't get or wish you could have had, we tend to bring those fashions back,” says Jim Jones, who even released a Dipset collaboration with B.B. Simon at ComplexCon in 2023. “I believe that's what has happened with B.B. Simon. Over and over.”