It’s hard to recall a time when this many black female photographers and directors were being hired to work on high profile projects. There’s been directors like Julie Dash, who wrote, directed, and produced Daughters of the Dust, in 1991—it was the first feature film directed by a black woman distributed theatrically in the United States. And there’s photographers like Carrie Mae Weems and Deborah Willis who have documented black life over the past couple decades. They have all helped open doors, but it took a while to get to this place.

This flourishing time for black photographers has been documented by Antwaun Sargent in his book, The New Black Vanguard: Photography Between Art and Fashion. It features essays and photos from black photographers of today. And we wanted to hear more from some of the women who are helping the industry get to a new place. So we brought Dana Scruggs, Flo Ngala, Adrienne Raquel, Arielle Bobb-Willis, and Lacey Duke all together over Zoom.

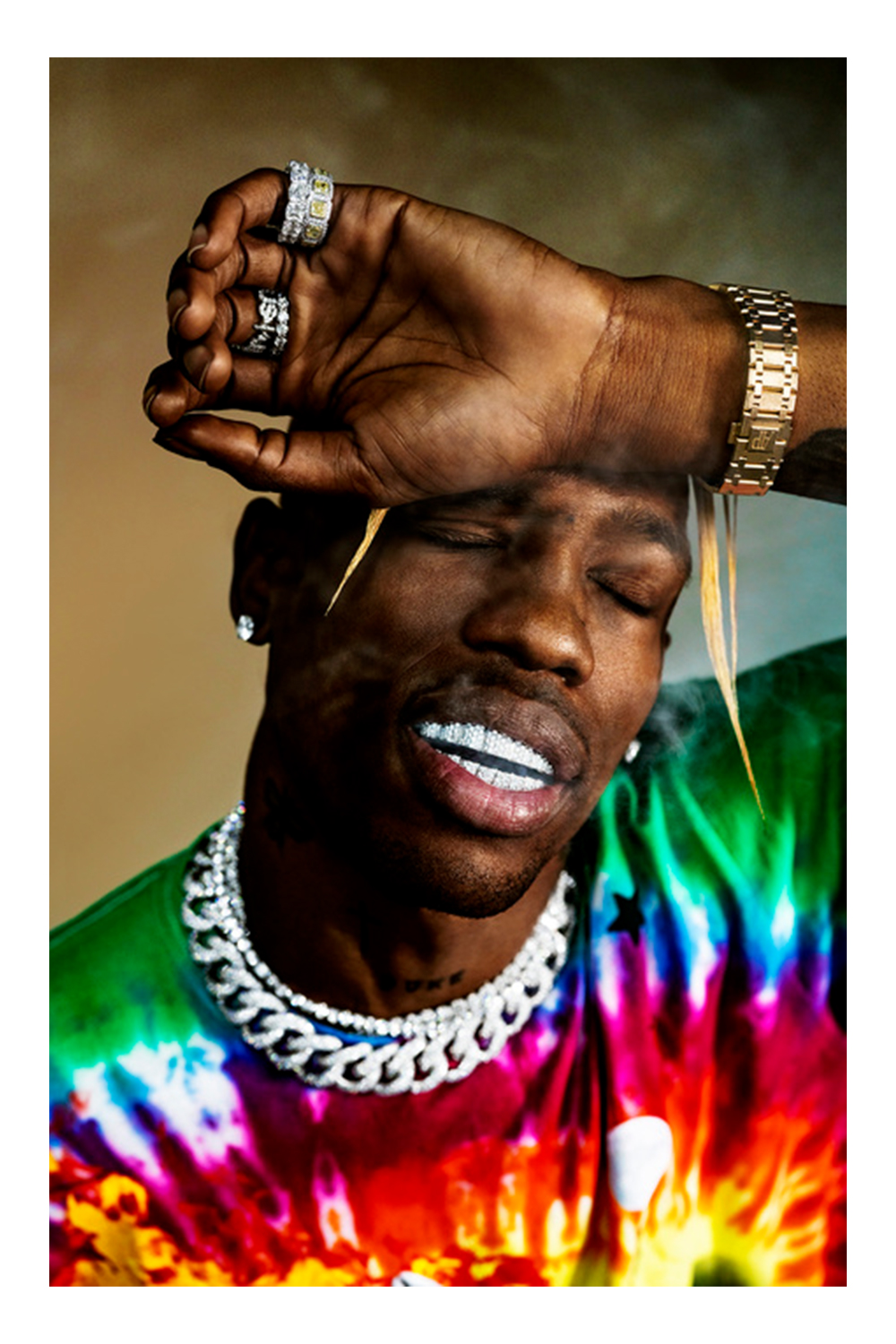

Dana Scruggs fell into photography. The Chicago native started taking pictures of models wearing vintage clothes for her Etsy shop. She went on to shoot more models in Chicago before moving to New York and creating her own publication, SCRUGGS Magazine. It featured her photography, which focuses on the male form. An editor seeing her work online led her to shooting track runner Tori Bowie for ESPN’s 2018 The Body Issue—she was the first black woman to shoot an athlete for the issue. She went on to become the first black woman to shoot the 2019 edition of the issue when she captured gymnast Katelyn Ohashi for the cover. In 2018 she shot Travis Scott for Rolling Stone's December issue and she became the first black person to shoot a cover in the magazine’s 50 year history.

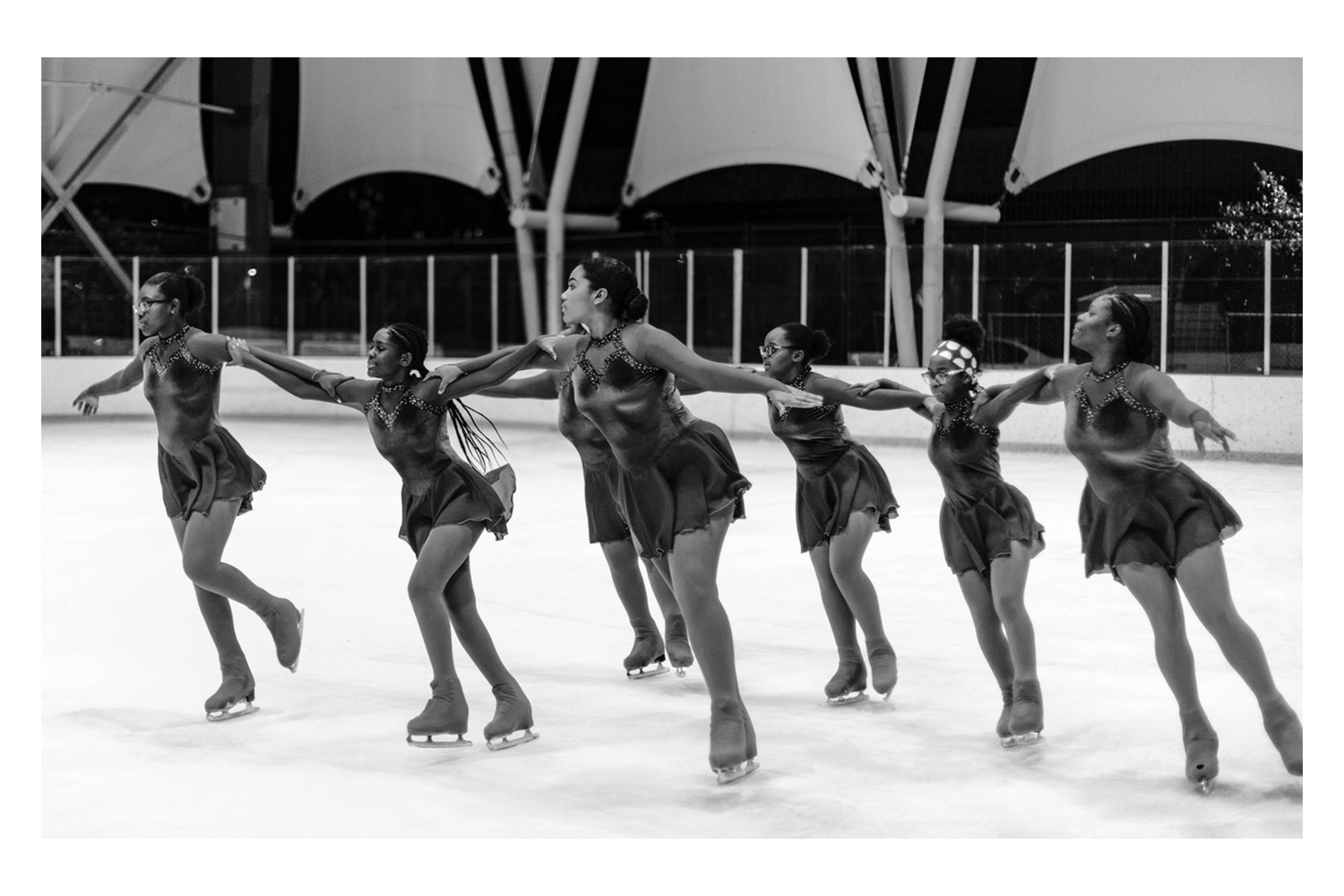

Flo Ngala, who was born and raised in Harlem, studied advertising and intended on being a creative director before falling into photography—she took photography courses in high school. A friend invited her to a Fat Joe and Remy Ma video shoot and she brought her camera, took pictures, and sent them to the director of the video who liked them, and shared them with someone at Atlantic Records. That led to her shooting Gucci Mane and eventually becoming Cardi B’s personal photographer. Ngala has also shot the Figure Skating in Harlem program—a photo of the skater’s legs ended up on the first page of the New York Times, and has documented events like the Broward Carnival in Miami and the African American Day Parade in Harlem.

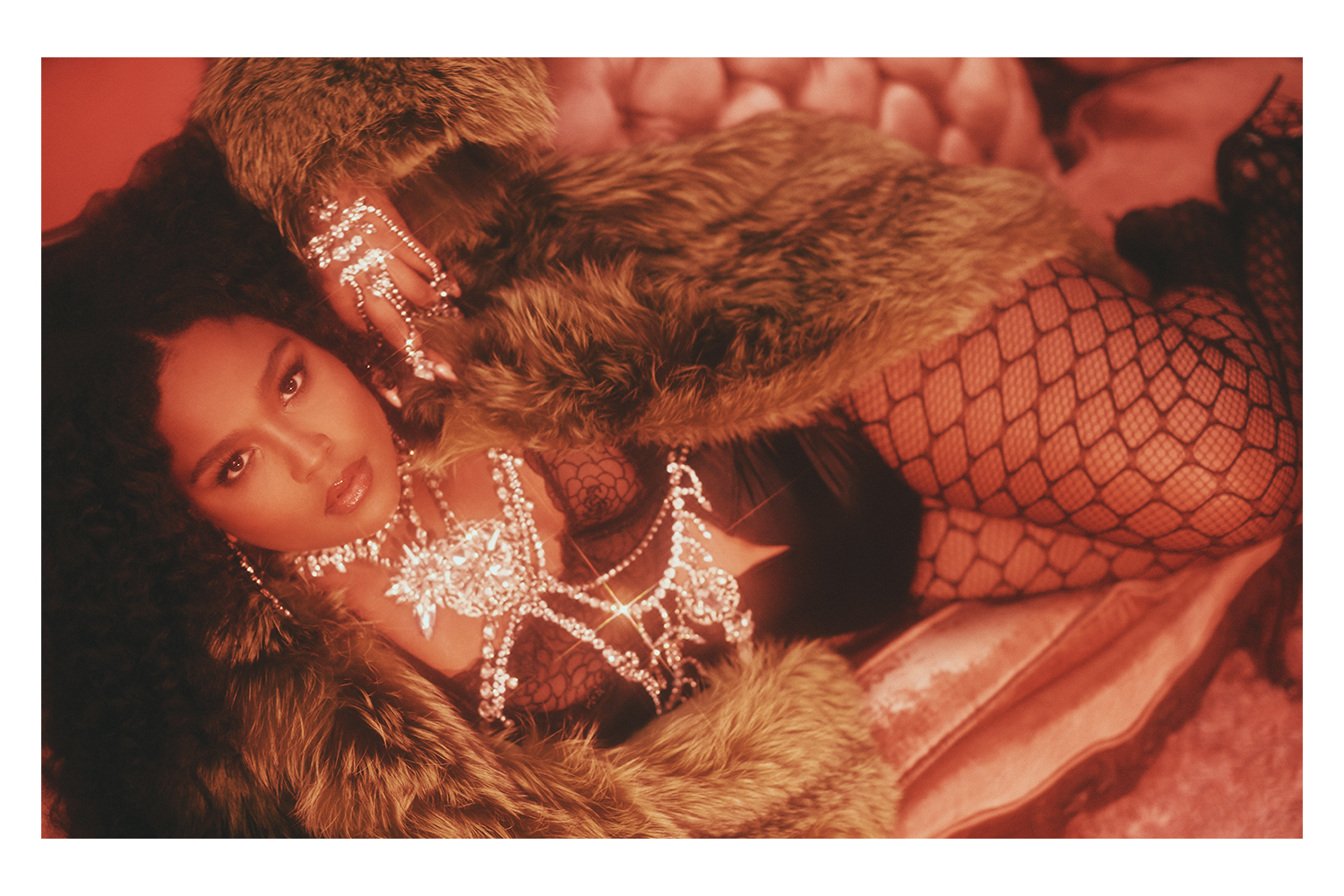

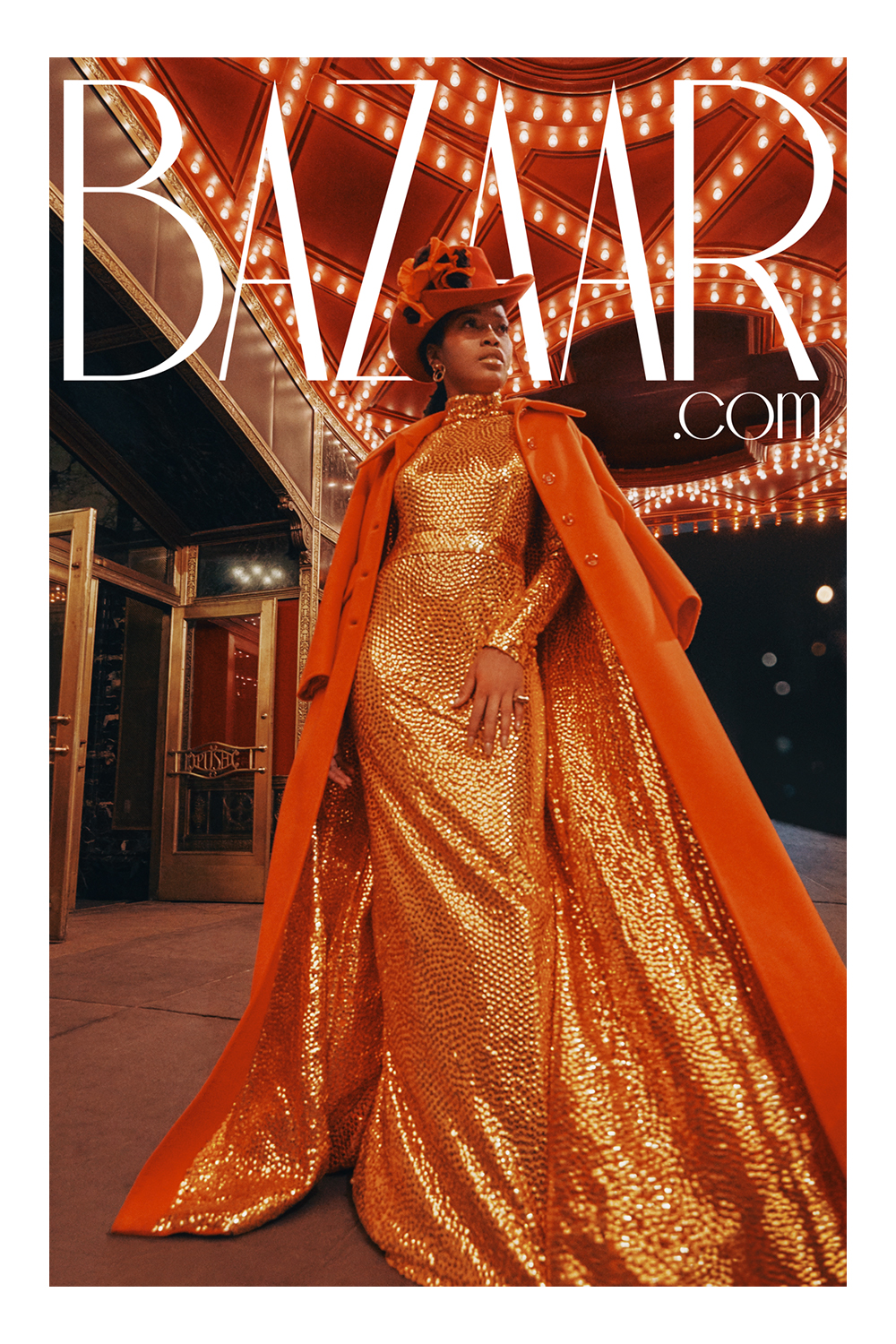

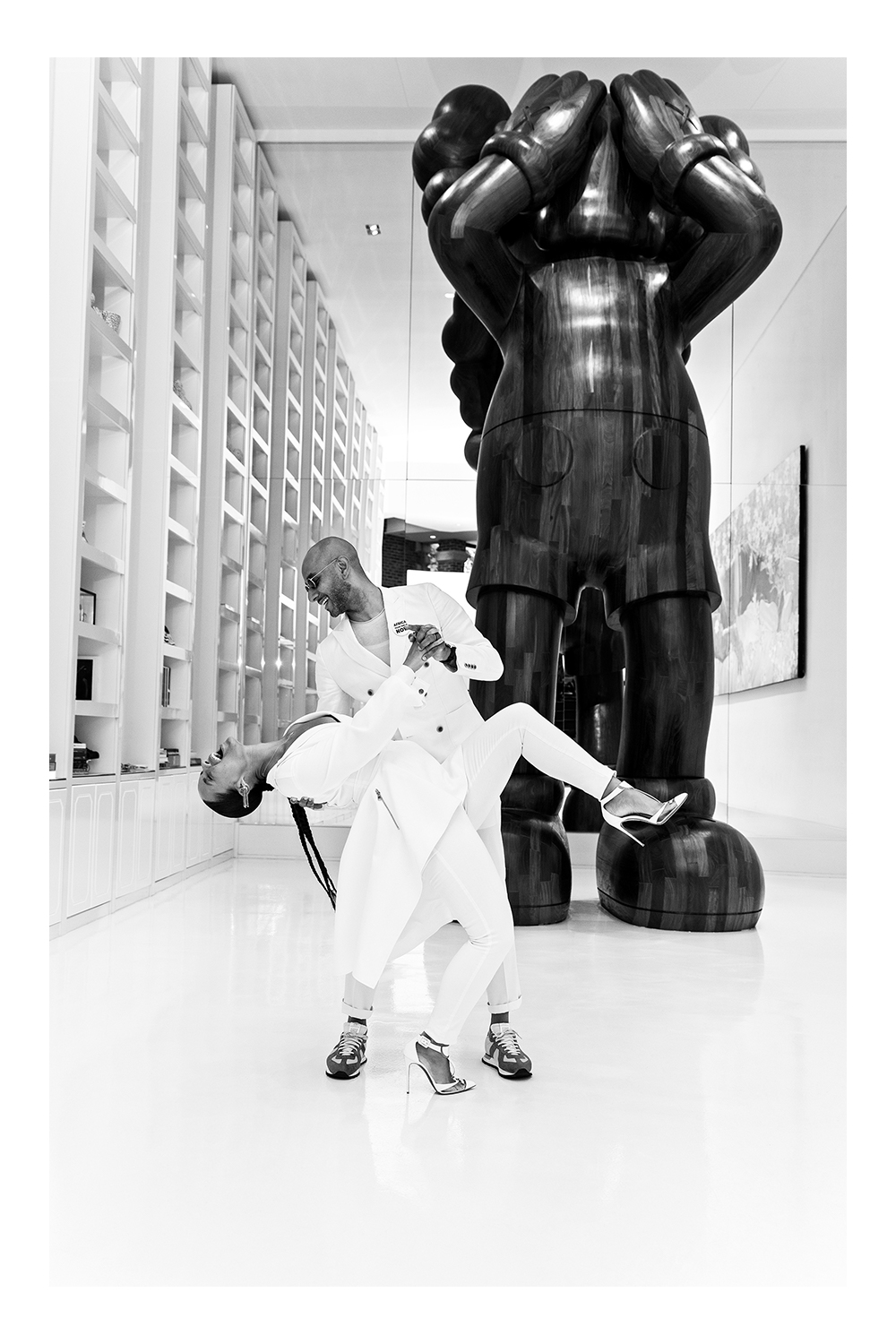

Adrienne Raquel, who grew up in Cleveland, Ohio before moving to Houston at 17, headed to New York after graduating with a degree in journalism. She took a photography class while attending the University of Houston, but wanted to work in the photo or art department at a magazine—she interned for Complex’s art department in 2012. She landed a job as a junior producer at a production company but started investing more energy into her Instagram page that was full of mostly still life shots saturated in color. She started freelancing as an art director and transitioned into shooting more portraits once she was signed by IMG Lens. She shot Lizzo for the March 2019 issue of Playboy magazine and has also shot Keke Palmer and Megan Thee Stallion. She’s known for her lush, dreamy imagery.

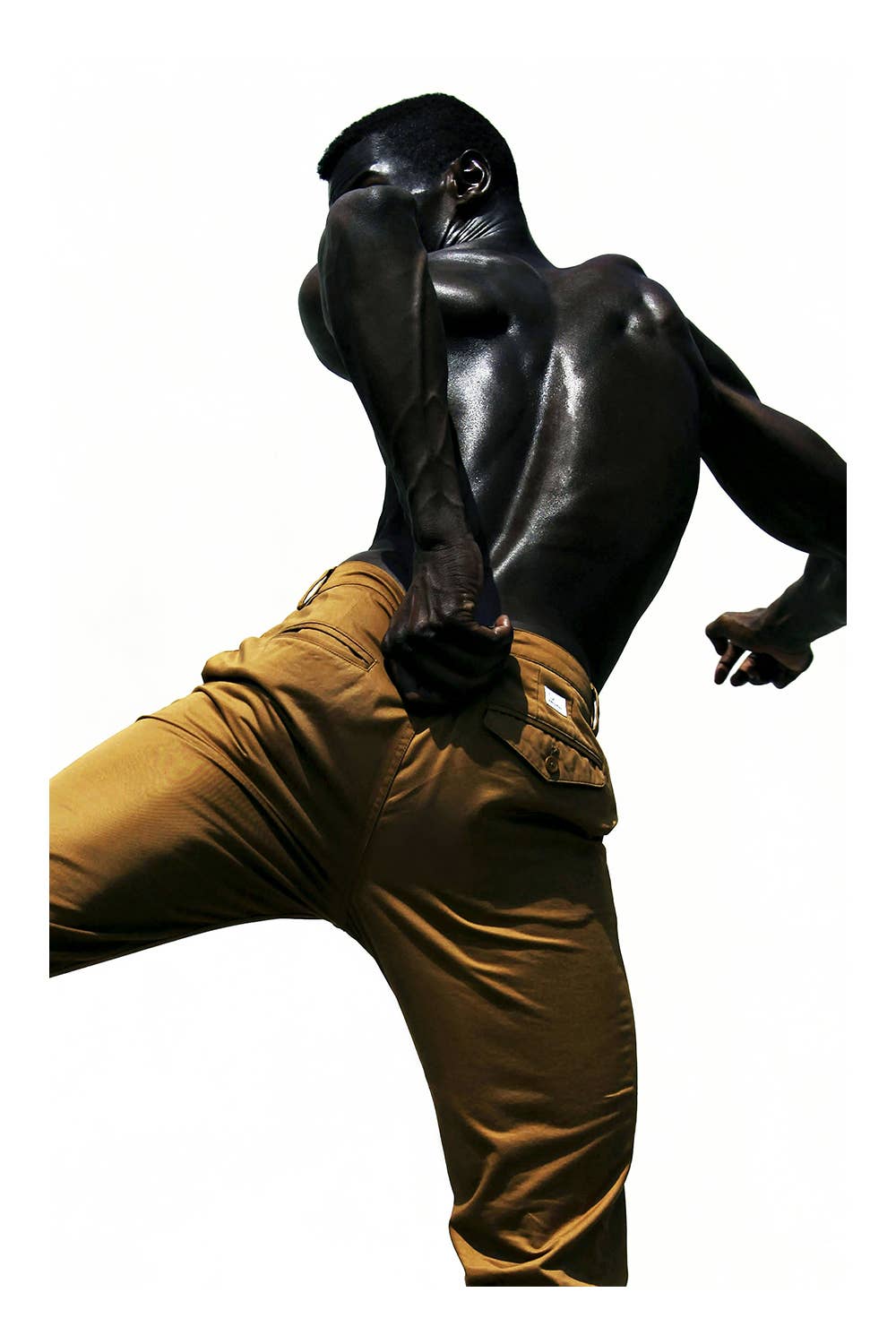

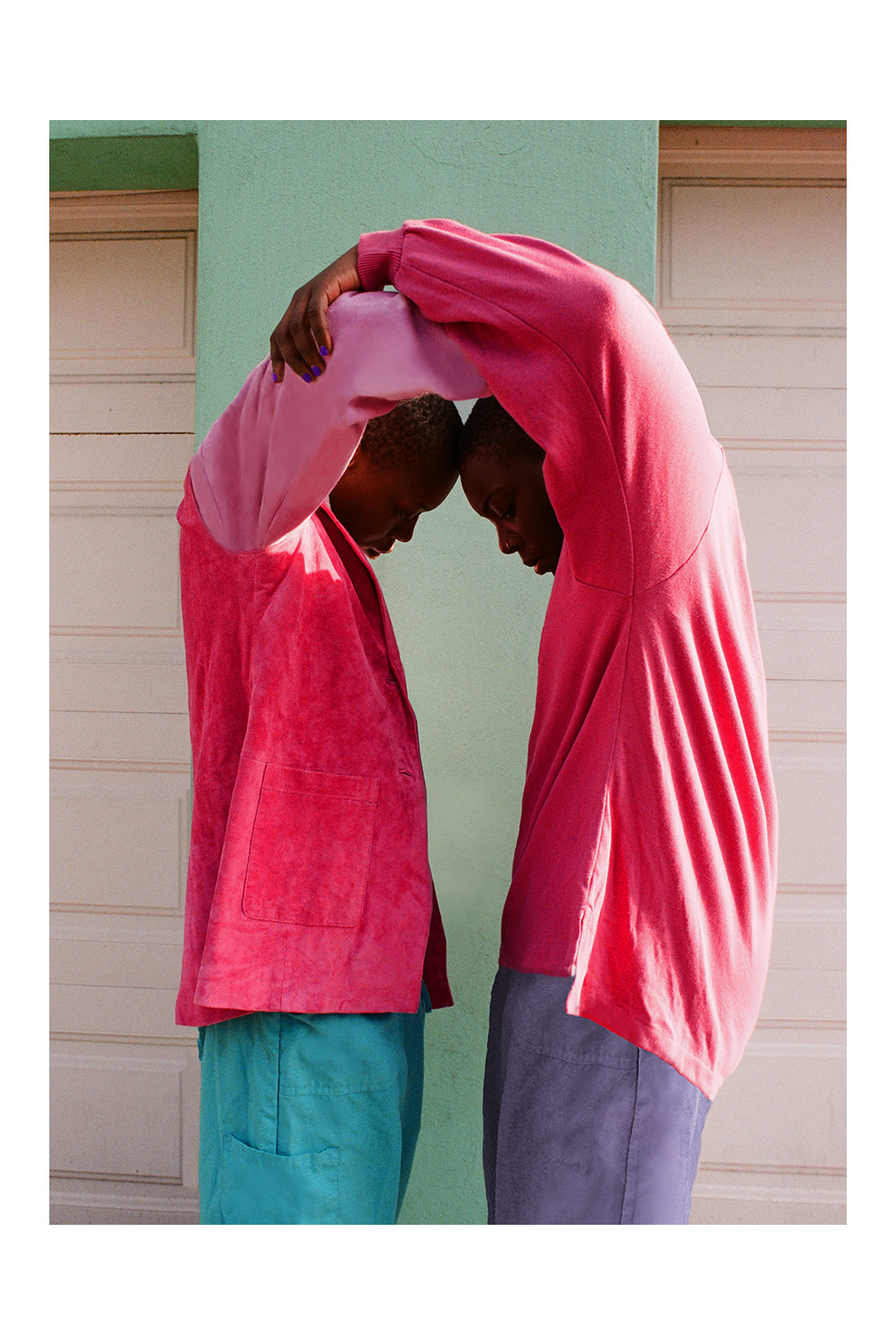

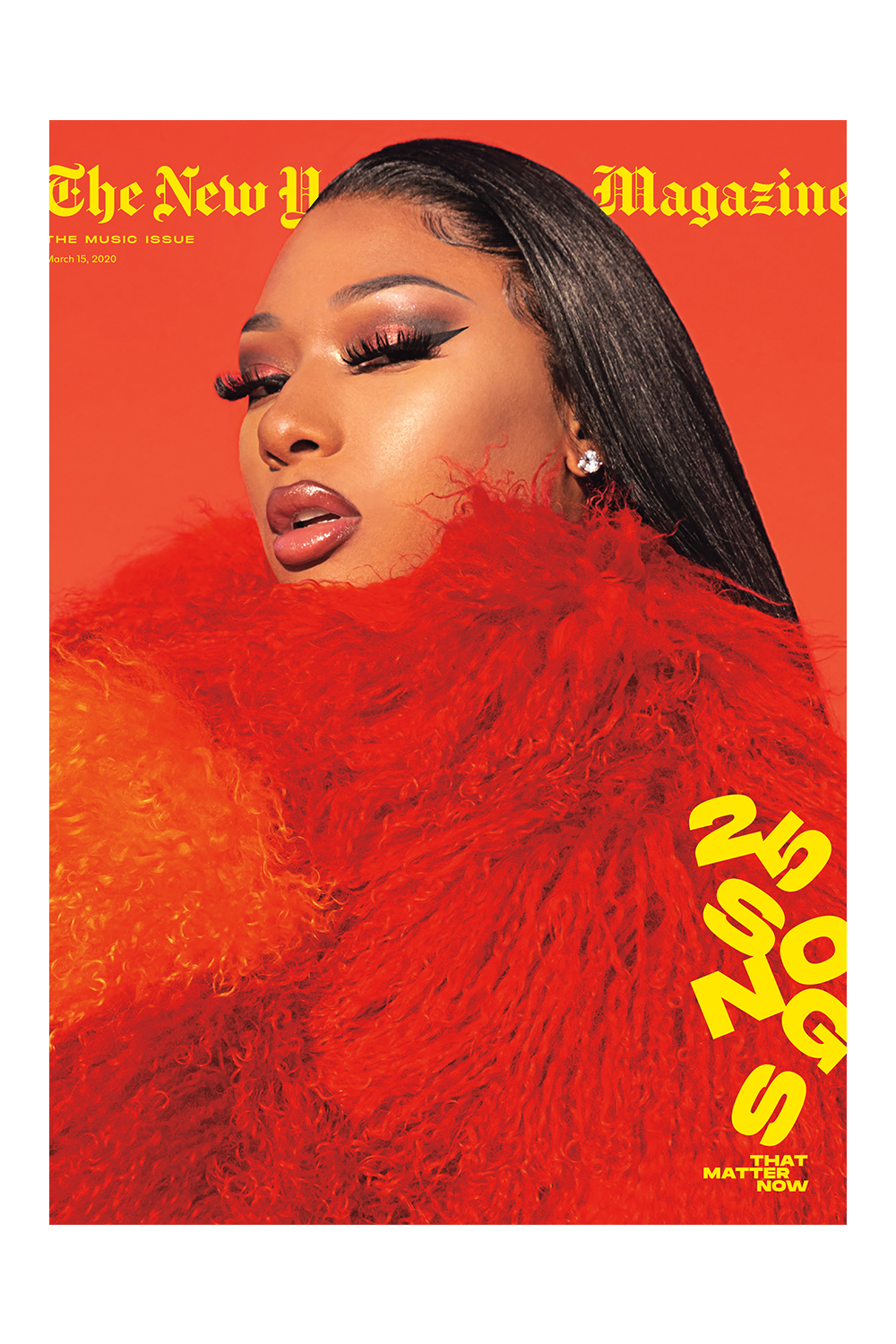

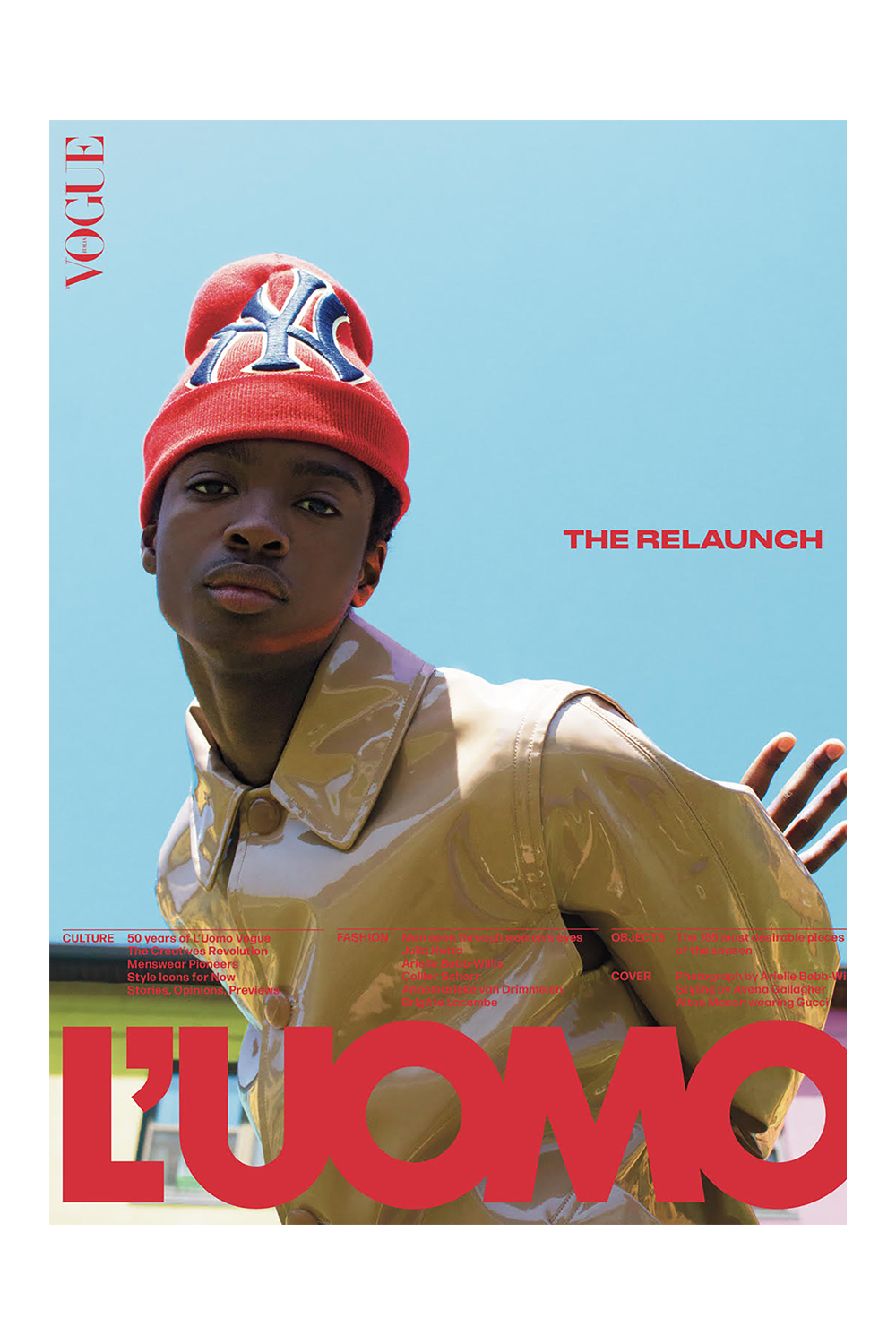

Arielle Bobb-Willis spent her early adolescence in New York before moving to South Carolina where she took a photography class in high school and fell in love. She went to New Orleans for college, but dropped out after some time, worked at Buffalo Exchange, and created photos with friends. She eventually moved back to New York, worked in Beacon’s Closet, and continued to make more photos. She developed a style centered on color, faceless images, and arresting body positioning. Her work caught the eye of Sargent, who wrote about her in The New Yorker. That led to her shooting Alton Mason for the cover of L'Uomo Vogue—she's the first black woman to shoot a cover for the publication. And she photographed Billie Eilish, Megan Thee Stallion, and Lil Nas X for New York Times Magazine's annual Music Issue.

Lacey Duke, who grew up in Toronto, discovered Hype Williams and knew she wanted to be a music video director. So she went to film school then interned at a production company in London and later transferred to New York. She created videos with smaller artists that she usually paid for, but things changed when she went to a Janelle Monáe concert with a friend and met her after the show. Monáe would work with Duke, who eventually moved to Atlanta, on smaller branded projects before asking her to direct her music video for “I Like That.” She’s since directed Netflix’s Strong Black Lead commercial, an episode of Ava DuVernay’s Queen Sugar, and an episode of Issa Rae’s Insecure.

These women might not realize it now, but they are ushering in a new era and changing the industry in profound ways. Here’s what each of them had to say about this pivotal time and what it’s like to be a part of it.

(This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.)

What do you say to people who say, ‘It doesn’t matter who is taking the picture? As long as they can take a good picture?’

Adrienne Raquel: There's obviously a difference between a male shooting a woman and a woman shooting a woman. Throughout history, photography has been dominated by white males. It's just different. We're black people, so how we capture the subtleties and view each other is inherently different from other people. We all have narratives. We all have stories to tell and that just naturally translates when we capture one another. And there's a sense of pride that comes with that. It's just special.

Dana Scruggs: Anybody can shoot anybody of course, but I think it's important that black people, and especially black women, are shooting other black people. White people have been documenting black people since the beginning of time, or since the beginning of photography - and exploiting us. We're not reaping any of the benefits of the documentation of our culture. And if you look at hip hop photographers, all of the people that documented the early days of hip hop, not all of them, but the majority of people who are making the most money off of the documentation of the early days of hip hop are white people. I think black people finally getting the opportunity to document our people in a way that we're financially benefiting from it, is extremely important.

Lacey Duke: For me, I have a rapport with Summer Walker. There's a comfort there. I care because I am also a black woman and I want to be presented in a certain way. And it's frustrating when that care is not taken. Some directors may just be more concerned about getting the shot and not presenting this black woman in the light that she wants to be presented in.

For me that's extremely important. Communication is important. I usually demand some level of communication before I get on set because I want to know the person. I need to know what you don't like, what you like, what lighting you like. I take that extra level of care. I care that much about every single angle, every single shot, every single retouched moment. I'll fight for them because I see myself in the women I work with.

Arielle Bobb-Willis: I also feel like we have the responsibility to bring people of color into shoots. I’m always going to ask for a person of color on set, no matter what. It’s important we bring each other into those places to have those opportunities as well. In the beginning I was nervous about asking for things, but over the course of the year and doing more shoots or taking more meetings, I've definitely become more confident in asking for what I want, and realizing that I feel like there's a power in being a photographer on a set, like you can ask for what direction you want to go into.

But do you all start to feel pigeonholed by your subjects? Or do you feel like people only hire you to shoot certain subjects? And how do you kind of expand beyond that? Or do you even want to expand beyond that?

Flo Ngala: The pigeonhole thing is super real. I feel like imposter syndrome is also something I'm beginning to suffer with. Like just my own self-imposed pigeonholing and feeling like people started expecting me to be places or do things when you're associated with being a personal photographer for someone popular. I feel like it challenged me to prove to myself that this is not a box that I will be put in by any means. I was a photographer before I started working with her [referring to Cardi B]. If it never happened with her, I still would've pursued photography to the highest level that I decided to. But having shot Cardi allows me to go to bigger platforms and be like, ‘Hey, this is what I've done. But also look at my other work.’ My interests are not just shooting celebrities or working with celebrities.

I almost used to be insulted by it and be like, ‘Damn, you know nothing else about my work,’ but now I understand a bit more that it's obviously not insulting. It's just like this is part of your come up. This is part of your career. And it's a big part of it. It's up to the photographer though, ultimately, to decide if they want to break out of that pigeonhole box or if they want to stay within those, I guess perimeters.

LD: I agree with Flo. There was a moment in my career where I thought I had to be more mainstream or essentially work with white people. But currently, I love that bag I’m in. I have a responsibility in a sense, and I don't feel pigeonholed by it at all. I think there's something beautiful about my subjects just being black women, that's not some little shit. That's not some like, "I just shoot black women." No, I shoot black women. I can do that in the form of a music video, or I can have a black woman be the protagonist in my feature film, or an episode of TV that I direct. I’m proud that most of my subjects have been black women throughout my career.

DS: For the bulk of my career, I mainly just focused on shooting black people and especially black men. And that was the only thing I was really interested in. And then things started happening for me outside of the self assigned work that I was doing. And I realized that I'm open to shooting everybody. I always want black people, and especially black men, to be the core of my work. But I realized that I want to document the people of this time. I don't want to be pigeonholed into only shooting black people for publications or for commercial work.

DS: What I started doing was sending lists to all of my photo editors that I have relationships with and telling them who I want to shoot. It's usually a mix of black people, white people, people of color, people that I'm interested in photographing. I just saying to them, ‘Please keep me in mind if any of these people have editorials or projects coming up with your publication.’ I think that helped, because then I started getting other people like Pete Buttigieg, who is kind of an outlier for someone like me to shoot. But I was happy to do it because it's like, okay, this is a challenge for me. And also to shoot him in a way that as a black woman, nobody really has shot him before. When I die or when I'm 80, I want my archive to be diverse. I want my archive to document people from all of these eras, and you can look at that photograph and see this was that era because of this politician she shot, or this social justice person she shot, or this celebrity that she shot.

As women, how are you all navigating directing what’s happening on set?

AR: Unless I know my client beforehand, most people assume that I’m the makeup artist. And people are always either shocked or I have moments where people try to do this weird one-up thing and I’m like ‘Dawg, we're just here to work. There is no time for drama, let's get it done.’ But as far as navigating sets, it took me a long time to get comfortable. Naturally, I'm a really soft spoken person. So, I had to get comfortable with speaking up and realizing that I'm the person in charge. Because in a lot of my shoots, I literally dictate everything from the set design, makeup ideas, and clothing. It just took time to get accustomed to that. Then, to also realize that I'm in this place and this space and having these opportunities for a reason. There's been moments where I had to set aside the self doubt and just be like, ‘Look, bitch. You must do this and you must kill it.’

I get my eyes on everything and I try to give my input on all of my shoots. Before we actually start shooting, I float around. I float over to hair and makeup. I float over to styling. I float over and see what's going on with set design. I check in on my assistants, and like literally every little thing, I give some type of input on or constructive criticism or I'll just say, ‘Hey, do you think this would look better if we wore this, or do you think we should change that out?’ I try to make it as much of a collaborative process as possible, but I just speak up and make sure things look the way that I envision them looking.

LD: The thing is with music videos specifically, there is no time. The minute you get there, you're running. You're running the whole day, so I'm just like, "Hey, you all. It's me. I'm here. What's up? What do you need?" Then, I go and get acquainted with my client and see what they need, give them the rundown of the day, give them an overview of the first scene, and float around and just communicate as much as possible, but it's a constant learning experience to find that balance of being assertive, being in control, but also not scaring people. You have to be nurturing and you have to be sweet to your clients. Then, as a director, you're like a low key psychologist. You have to know how to consider feelings and consider people's moods because you're going to be working for 20 hours together, sometimes two days in a row. It’s a balancing act.

How are you deciding what to say ‘no’ and ‘yes’ to?

DS: When everything started to hit for me after ESPN's Body Issue, I did say yes to everything because I never had most of those opportunities that were coming to me. It was exciting. I didn't really think about things like trajectory and is this actually something else that's helpful for me. I was also just trying to pay my rent. Once you get to the point where that's not an issue, you should definitely be more selective and start realizing that maybe this publication isn't the best publication for me to shoot for, regardless of who I’m shooting. And realizing that with celebrity, these people will come back around. And if you wait for them for something else that's within the vein of what it is that you actually want to do, then the wait will be worth it. But just shooting celebrity just for the sake of shooting celebrity will just get you in a really commercial, uninteresting, bag.

FN: I still struggle with saying yes or no to things because I haven't figured out what that looks like. I almost feel I have to justify why I don't want to do something. Maybe it's subconsciously a result of how the world identifies me and the freedom I feel I have with those identifications. It’s something I’ll find power over soon but it’s sad sometimes. I don't even feel like I have the right to just be like ‘No. Period. That's it.’"

So it's a crazy balance, and I think that's also the reason why sometimes saying no, and taking a break for your own sanity, you have to do that. Like right now, it's a great time for someone like me. It's great to take a break and get back to me and prepare myself to go back out into the world because it can get very draining over time. But it is survival mode when you're out there. You're literally going out there to check your ego but also survive, and then come back home and try to build yourself up again.

Let’s talk about ownership and what you all are doing to make sure you own your work?

ABW: I copyright all of my work. It takes kind of long, but it protects you. Also reading over contracts is super important. But also, just having the talks before you do the shoot. Asking how long the publication or company will own these photos? I talk with my agent about that all the time. Some clients are going to be like, ‘I want it forever. And you're like, ‘Forever?’ It's scary. I feel comfortable with them owning the images for a year or two.

So just having that conversation about what you're getting into, just knowing everything, being in every pocket that you can be when it comes to just protecting this thing that is so important to you. But yeah, I don't know about you guys. How do you go into protecting your images and everything?

DS: If it's a bigger company, and if it's not something I really care about and the rate is good, I'll give up my copyright for stuff like that. But for editorial, I feel like it’s not okay for magazines or for celebrities to try to infringe on copyright. I've been running into this several times, where a celebrity wants you to seek permission from them to use your own images, or they want approval of anything you post. For me, I'm like, ‘I got paid $500 to shoot you. I'm not going to sign a contract.’ I'm not going to be 80 years old and reaching out to try to find out who your representative is so that I can show an image at a gallery or at my retrospective. You see all these OG photographers who have shot Madonna or hip-hop artists and they own everything. And they're still eating off of their work when they're like 50, 60, 70 years old. When people do stuff like that, they're saying, ‘It was a privilege for you to shoot me because I'm a celebrity, so I need control over my image.’ But, I'm like, ‘No. I created this work and legally - I own this work. Photographers shouldn't be browbeaten and threatened into giving up creative control of our work when we barely even got paid.'

LD: On the TV side, if you’re hired as a director to do an episodic, you don’t own anything. There are unions in place to make sure you’re paid fairly, etc. We do get residuals and our fees as directors, though. So that's the great thing about TV and that's one of the reasons why so many directors want to break into TV, The pay is great. On the music video side, you own nothing. It's not a thing. But since streaming has become very lucrative in the music business, people are having conversations about ownership, but I honestly don’t see anything changing in the music business. If I have a hundred million views of a music video, I don't make anything from that, the label and the artist do. I just get a fee, if there’s anything left in the original budget. But it's kind of ridiculous because that was my idea, right?

What do you say to the idea that this influx of black photographers is a trend?

LD: For film and TV, I think there's hope. Mainly because you have a lot of black creatives that have made themselves businesses. You've got Issa Rae, you've got Lena Waithe, Ava DuVernay. All of these creatives are businesses. They're producing the content we watch and without them, I wouldn't actually be directing TV and film. My very first TV gig came through Ava DuVernay. I worked on a commercial with her a few months prior and she asked me what I wanted to do, I said direct more TV, she thought I was completely capable of doing that. So when she called me to shoot Queen Sugar, I had absolutely no TV experience, but she has the power to do that.

And she's not going anywhere. She’s giving the next generation of storytellers a platform. From working on Queen Sugar, I was hired to direct Insecure, And that's Issa Rae. She is the creator of that show. She's a black woman who has power and is like, ‘Oh, I want this black woman to direct this.’ So now there are a lot of black creatives becoming the business behind what’s happening. It wasn’t like that in the past. So yeah, I hope that continues. I think we're on the right path.

DS: I think with the question of are you afraid that things are going to dry up or that this is a wave? I think I don't necessarily have that fear that this is a wave and jobs will dry up. I think my fears are mainly rooted in just me being really outspoken and talking about whiteness, and racism, and problematic people— not by name—because that would really probably end everything, but just discussing my experiences. And this is such a new thing for me. Within the last two years my whole life has changed from it just being me and the model, to me being on these huge shoots dealing with teams of people, and having multiple people to please and answer to. And for the most part it's been fine, but there have been times where there have been issues. And I feel like it's important to talk about that because I think with this wave you see a few black photographers that are kind of making it and doing well. And I feel like people are thinking, ‘Oh, this is great and there's more opportunities.’ And yeah, there are, but there's still more work to be done.

FN:I don’t think it’s a trend. At the end of the day we are all black women. And yes, some of us choose to capture subjects that are exclusively black people. Sadly there are brands and companies that are going to hire us more so for marketing than perhaps for the work. But what I like to believe and focus on is being a good photographer, period. I’m a black, I’m a woman, I’m a good ass photographer. Those aren’t mutually exclusive and shouldn’t be considered only when it works for someone’s strategy deck or creative. Those identifiers aren’t besides the point. That is the point.

DS: Just to piggyback on that a little bit, I think once we get to the point where you can be black, successful, and mediocre - then we'll be able to say that things have actually changed. Because other people can be mediocre and be incredibly successful in this industry - or any industry really. Mediocrity is celebrated and monetized unless you're Black. We have to work 10 times harder and be at the top of our game creatively to even get a modicum of the success that other people with a lot less talent get in this industry.

LD: I literally said the exact same thing, like weird that you just said that. I said, ‘The minute that we can be black, successful and mediocre we've made it.’ Because there's so many mediocre people doing what we do. And they're killing it.

AR: I agree with what Flo said. I think that above all else it's like, yeah, we're women. Yeah, we're photographers. We just happen to be black. And I think that that talent doesn't go anywhere. I think that in some capacity there's always going to be a need for imagery. There's always going to be a need for film. There's always going to be a need to create things, to advertise things, etc. There's always going to be a need for it. And as it relates to myself, I'd like to look at myself outside of just being this black photographer of the moment. But I don't know, maybe I'm naive.

ABW: Yeah. I agree with what everyone was saying. I feel like I'm going to create no matter what. I mean, I didn't get into this to be the first black anything. I did it because I love creating. I love learning and growing and just shooting. That's what I love. Maybe it's bad that I don't think about it ending, or me stopping. That doesn't really cross my mind too often, because even before this was my job, I never questioned stopping. Like even if people are like, ‘You want to be a photographer?’ I was like 'Yes, this is what I'm going to do forever, for the rest of my life.' So yeah. No, I don't really bring that energy into my space, I guess. And I totally agree with what everyone was saying.