Tremaine Emory’s appointment as Supreme’s creative director marks one of the brand’s biggest moves since being acquired by VF Corporation in 2020. Brendon Babenzien and Angelo Baque served as brand directors at the streetwear brand, but this is the first time Supreme has publicly confirmed an external creative director hire.

Emory is no stranger to Supreme. In past interviews, he has expressed his admiration for the brand and said he was friendly with its founder, James Jebbia. But Emory built a name for himself with Denim Tears, a clothing label that releases highly coveted garments tied to rich narratives about the African American experience. Denim Tears’ most popular releases are Levi's jeans covered in a cotton wreath motif—their first collaboration in 2020 was so successful that it led to Emory signing a two-year partnership deal with the brand last year.

“Denim is made from cotton. America is made from cotton. The Black experience started with picking cotton. So, Denim Tears,” Emory told The Face. “Metaphorically if you look at a pair of jeans or any garment that’s cotton, it traces all the way back to that.”

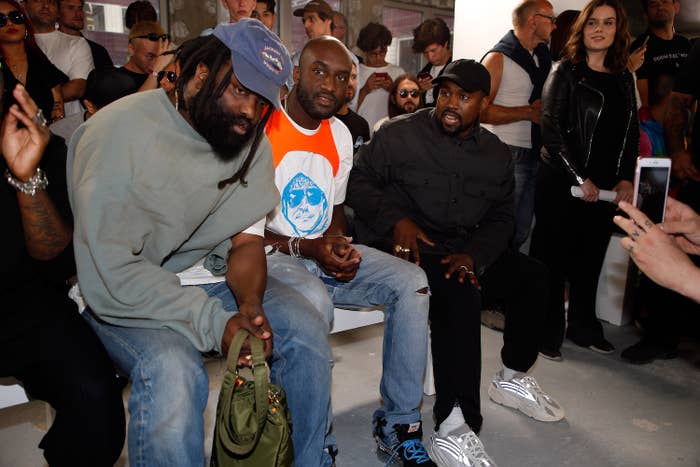

Much like his contemporary, Virgil Abloh, Emory represents a new class of designers who have redefined what a graphic T-shirt, hoodie, or sneaker can be. They both learned from the school of Supreme. But unlike Supreme, Emory approaches storytelling differently. He’s committed to forefronting a meaningful message as streetwear becomes more intertwined with hype and resale value. Last year he released a collection at London Fashion Week that shed a light on the plight of Caribbean immigrants in the UK who are apart of the the Windrush generation; he produced a knit flag sweater named after Tyson Beckford, a legendary Black model for Polo Ralph Lauren who made millions for the WASP-y American clothing brand; and released a David Hammons-inspired Converse collaboration that became a call to action for Nike to make actual commitments to diversity. Emory has never been afraid to use clothing as a vehicle to distribute knowledge and influence change.

“It’s like the Bee Gees song. ‘How deep is your love, how deep is your love, I really need to know.’ Are you just going to slap David Hammons and Marcus Garvey’s flag on this and make some money, or you going to help Black voters matter?” Emory told Complex, when speaking on his decision to delay the release of his 2020 Converse collaboration. “I also wanted to show people you can speak out and it’s OK, you’re still going to figure out how to pay for your rent, you’re still going to eat. Whether Converse would’ve dropped me or not, it doesn’t matter. What matters is talking about this thing. We can put all sorts of bullshit on Instagram, but let’s put some real shit up.”

And that’s why Supreme needs someone like Emory as its creative director.

Supreme holds a rich history. In 1994, British entrepreneur James Jebbia opened a skateboard shop in SoHo with a vision to create clothing that catered to downtown New York kids. In its earliest days, Supreme’s much-coveted box logo T-shirt wasn’t a symbol of wealth. It was a crest that represented a tribe of rebellious skateboarders who shredded the streets of New York. As the brand grew, Jebbia began to mirror designers like Ralph Lauren. Whereas Ralph Lauren situated Polo under a rose-tinted vision of Americana, Supreme created a universe of its own built off an idyllic vision of not just ‘90s New York, but urban culture at large. It’s why Supreme has collaborated with famous Amsterdam graffiti pioneers such as Delta or brands popularized by New York City rappers in the 2000s like B.B. Simon.

But what’s often missing from Supreme is context. A large part of the allure of many popular streetwear brands is being built off of a premise of “if you know, you know.” A windbreaker from its 2005 collection mimicked Polo’s Stadium 1992 jacket, a piece popularized by the Brooklyn Lo Lifes. A new fleece jacket in their Spring/Summer 2022 collection boasts a typeface on the back that was popularized by New York City breakers from the early years of hip-hop. However, Supreme will never spell this out for you. Sometimes, they’ll release a short one to two-minute video briefly explaining some of their collaborators in the “Random’’ section of their website or their social platforms. But the brand largely remains esoteric.

While creating mystique around a line isn’t new in fashion, at times it could backfire. Last season, that became clear when Supreme released a collaboration with True Religion and another iteration of a 700-Fill Gore-Tex down jacket covered in New York Yankees logos—a silhouette that’s known in certain New York City neighborhoods as the Marmot Mammoth Parka or a “Biggie” jacket. For some it was just another hyped Supreme release, but for certain New Yorkers, it was offensive.

Mikey Phelps, an Instagram influencer from East Harlem released his own version of a New York Yankees Biggie jacket in response to Supreme continuing “to steal ideas from people in the hood for their profit.” Similarly, a Bronx-based Instagram influencer named Malachi Gomis also accused New York-based streetwear brands like Supreme, Kith, and Aimé Leon Dore of stealing and appropriating fashion trends popularized by people of color from the Bronx and Harlem in the late 2000s.

“It really bothers me to see white boys in SoHo wearing gray bottoms, B.B. belts, and Uptowns, in the name of ‘streetwear,’” wrote Gomis. “Because a few years ago in The Bronx, at least 100 Black and Latinx kids who were my age and from my neighborhood, were profiled and indicted for this style shit we started.”

Cultural appropriation has come up a lot within the fashion and streetwear space over the past couple of years. And with Supreme being so closely tied to a secondary market built off hypebeast entrepreneurship, the brand’s clothes start to lose their intended meaning and feel more like a tradable commodity with the revenues not benefitting these communities. Like many other brands, during the tumultuous racial justice protests that occured throughout summer of 2020, Supreme also responded by revealing they made a donation of $500,000 split between Black Lives Matter, Equal Justice Initiative, Campaign Zero and Black Futures Lab. But for many people of color, wearing the type of clothes Supreme sells can still affect how the public perceives them. While hoodies have become a ubiquitous lifestyle garment today, it was no less than a decade ago when Trayvon Martin was seen as a threat for wearing one. While some may have smirked at Kanye West’s comments revering the hoodie as “the most important piece of apparel of the last decade,” he certainly wasn’t wrong when remembering major protests like the Million Hoodie March. The larger symbolism behind these garments is weaved into the very name of Emory’s own label, which puts emphasis on weathered denim jeans—another popular article of clothing that’s historically been tied to misconceived stereotypes within communities of color.

“The handle [Denim Tears], it keeps evolving, but it’s a metaphor for attrition of life,” Emory told Jeff Staple, in a Hypebeast Radio interview in 2019. “The jeans people value the most are the ones that they’ve worn for a long time. The beauty is what the jeans have been through and that’s life.”

In that interview, Emory went into great detail about his upbringing and how he became an influential creative within the fashion industry. Born in 1981 in College Park, Atlanta, Emory moved to Flushing, Queens with his family when he was just 3 years old before moving to the historically Black neighborhood of Jamaica, Queens when he was 10. A child of the ‘80s and ‘90s, his memories included seeing famous gangsters like Ronnie Bumps of the Supreme Team and watching local New York hip-hop celebs like DJ Clue get cuts in his local barbershop. Although Emory told Staple he was fascinated with style since he was a kid, he learned a lot about fashion from his New York upbringing. In the interview, he reminisced about being a “Union rat” back when they had an outpost in New York, buying sneakers at Nort, and being the first to wear Prada Sport sneakers in his neighborhood.

“First time I’ve ever seen seeding, I was getting my haircut and DJ Clue was in there and he had the first ever Foamposites,” Emory told Staple. “I was like what are those? And he said: ‘Oh these are the new Penny Hardaways, Nike gave them to me early.’ I couldn’t wrap my head around the fact that it was a DJ whose mixtapes I bought at the Colosseum Mall and not an athlete.”

Like Jebbia, Emory didn’t attend fashion school and got his start in retail. After graduating from Thomas Edison High School he briefly went to Laguardia Community College to study film and acting before dropping out. After growing tired of breaking his back loading hundreds of FedEx boxes a day for $8.50 an hour, and speaking out against anti-unionization efforts by higher ups, Emory quit his job to work retail. One of his first retail jobs was at J. Crew, which he also quit after managers told him he couldn’t keep his braids because it was “hair art.” He worked in stockrooms at department stores like Barneys New York, Saks Fifth Avenue, Bergdorf Goodman, Kate Spade, and even his own neighborhood liquor store. Emory revealed to Staple that during the early 2000s, he really wanted to work at Union and was close with the shop’s original owner Mary Ann Fusco, who opened the store with Jebbia. Jebbia was supposed to interview Emory for a job at Stüssy’s New York store, but the interview never happened. Instead, Emory got his first break in the industry at Marc Jacobs in 2006.

Emory told Staple he admired the label because it embraced placing employees of all genders and ethnicities in all kinds of positions. Emory worked for the brand for nine years and eventually became a manager at a Marc Jacobs store in London. That was his last 9-to-5 gig before he started to consult for artists like Frank Ocean and Ye, and helped revive brands like Stüssy as an art director. He also co-founded the influential creative platform No Vacancy Inn alongside Acyde before Denim Tears.

Emory’s background as a designer isn’t just non-traditional, and thus apt, for a brand like Supreme. More importantly, Emory emphasized in his interview with Staple that growing up in New York during the ‘80s and ‘90s taught him a lot about the human condition, which is deeply entrenched in his approach to storytelling. While a brand like Supreme will reference a cultural touchstone or moment and let the consumer piece the narrative together, Denim Tears sees the product as an opportunity to directly speak to and educate its audience.

“I kind of like [see] Denim Tears to me as Supreme for Black people and anyone else who wants to celebrate or commemorate what we’ve been through,” Emory told Najee Reed of the RSVP Gallery in an interview. “[It’s] using T-shirts as billboards for knowledge and expression.”

For example, Emory used his collaboration with Ugg as an opportunity to highlight Black Native American communities. The collection was named after his great-grandmother “Onia” who was a descendant of Black Seminoles—a group of free Blacks and runaway slaves who joined Seminole Native Americans in Florida between 1700 and the 1850s. He further expanded on the stories of Black Native Americans by releasing an hourlong documentary alongside it, directed by Emory, on the Mardi Gras Indians of New Orleans, who were photographed for the collection’s lookbook. When the collection dropped, Denim Tears also released academic books on the history of Black Seminoles and Mardis Gras Indians. Both brands donated $50,000 each to the Backstreet Cultural Museum and Guardians Institute—cultural institutions in New Orleans that are keeping these stories alive. Emory has also partnered with the Alvin Ailey Dance Theater and released a short film with Levi’s where he interviewed his elders about how cotton shaped their own experience in the American South during the early 20th century.

“I love Supreme. But I noticed every season, especially within the last four or five years, they do like, a Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, or Dead Prez hoodie. All that shit is dope but I noticed it never sells out,” Emory told the RSVP Gallery when detailing the idea behind Denim Tears. “It ain’t Supreme’s fault because they’re making it, putting it out, and want it. I salute James and his whole team, but I’m just like: ‘What if I did a whole sportswear brand based on that.’”

Post-2020, fashion is still figuring out how to forefront diversity and representation within the industry. Brands like Kith have agreed to become a part of the 15 Percent Pledge while New York City labels like Angelo Baque’s Awake has continued to give back to the communities in need that directly inspired it. It’s not like Supreme has never donated to charity before 2020—many of the brand’s popular box logo T-shirt releases are donated to timely causes or to communities their stores are based in. And of course, Supreme has always operated like a gallery that has constantly highlighted marginalized artists like the New York graffiti tagger Earsnot or the Dancehall album artwork of Wilfred Limonious.

But nowadays, especially when an underground reference can be discovered and analyzed in seconds by an Instagrammer armed with a reverse Google image search, is there really any need, or is it still even cool, to take such a boldly quiet approach as a brand? Is there enough room at Supreme to let some more voices be heard? Is there an opportunity to use their large platform to push the industry into a more interesting direction that fosters thoughtful conversations about the culture at large and less about the perceived resale value of a cotton T-shirt or hoodie?

So far, Supreme’s approach has worked. It has led the brand to being acquired for $2.1 billion by VF Corporation less than two years ago and has pulled, in the most recent quarter, $200 million in revenue for its parent company. But as the brand continues to grow bigger and reach more consumers than ever before, it must become more aware of how it will be perceived by consumers who desire something more than a brand’s glossy logo or limited stock. Whether it’s how clothing impacts the environment or the influence it pulls from marginalized communities, the fashion industry at large needs to become more transparent overall. And it needs to put more emphasis on giving back to the communities and subcultures that it’s constantly influenced by. Emory has proven that telling real, detailed stories about clothing is not crazy or overbearing. It’s incredibly compelling.