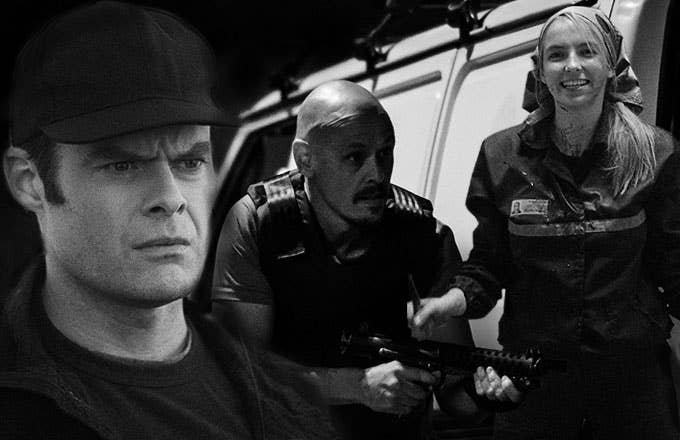

In the opening episode of the FX series Mr Inbetween, we meet a charming Australian man named Ray Shoesmith (Scott Ryan) and see his workaday life in Melbourne: walking his dog, picking up his daughter from his ex-wife’s house, and having an amusing conversation about a friend’s marital difficulties. You also see Shoesmith terrorize and intimidate people, and push a guy off the top of a staircase to his presumed death.

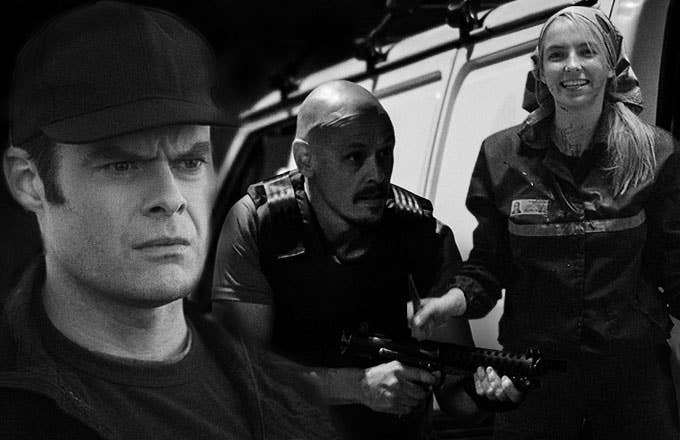

Shoesmith isn’t the only relatable hitman we’ve met on cable this year. A week before Mr Inbetween premiered in September, Bill Hader won an Emmy for his portrayal of the title character in HBO’s Barry, a professional killer who tries to leave his violent job behind for an acting career. And one of the night’s most buzzed-about nominees was Sandra Oh for her performance in Killing Eve, a BBC America series about Eve Polastri (Oh), a spy who finds herself strangely attracted to an assassin, Villanelle (Jodie Comer).

It’s not surprising that shows about the complex inner lives of contract killers are all the rage; after all, one of the most dominant tropes of prestige TV drama is finding vulnerability and humor in often violent or immoral protagonists, from The Sopranos to Breaking Bad. And one of the direct precursors to the HBO and AMC antihero dramas of the 21st century was particularly obsessed with hitmen: the ‘90s independent film boom led by Quentin Tarantino.

Ever since 1994’s Pulp Fiction introduced us to Jules and Vincent, a pair of mob enforcers bantering entertainingly about cheeseburgers and TV pilots in between executions, pop culture has been obsessed with charming hitmen. Up to that point, contract killers might have been villains or the hard-boiled protagonists of crime movies like 1964’s The Killers or 1972’s The Mechanic, but rarely depicted with such warmth, humor, and moral ambiguity. Pulp Fiction, alongside Luc Besson’s 1994 sleeper hit Leon: The Professional, about a hitman who adopts a 12-year-old girl, and Robert Rodriquez’s 1995 Mexican hitman opus Desperado, created an odd little boom of quirky hitman movies (1992’s broad comedy flop Blame It On The Bellboy, about hitman shenanigans in a hotel, probably influenced nobody).

The hitman comedy genre peaked with the entertaining 1997 John Cusack vehicle Grosse Pointe Blank, but otherwise, the ‘90s were inundated with fairly undistinguished Tarantino ripoffs, dark comedies, and gritty action flicks like 2 Days in the Valley and Things To Do in Denver When You’re Dead. Hitmen remained a staple of action movies in the 21st century, but there was a move away from humorous character studies and back toward shoot-‘em-up action flicks like the John Wick series.

The new wave of hitman protagonists on TV, however, moves back towards the tension between murder for hire and trivial daily life that typified the wave of movies birthed by Pulp Fiction. Though Killing Eve is a one-hour drama, it features whipsmart and disarmingly funny dialogue from creator Phoebe Waller-Bridge, who previously created the BBC comedies Fleabag and Crashing. Barry is dark and thought-provoking, but intermittently hilarious, a creative breakthrough for Bill Hader, who spent years as Saturday Night Live’s funniest and most versatile celebrity impressionist.

Mr Inbetween, based on Scott Ryan’s 2005 independent feature The Magician, drops the film’s mockumentary conceit but is still a comedy, albeit a very dark comedy. In the pilot’s most unapologetically sitcom-y scene, Shoesmith’s friend Gary (Justin Rosniak) gets in trouble with his wife for leaving a porn DVD in the house, and Ray nobly defuses the marital spat by claiming the DVD as his own. Even on the job, he’s occasionally oddly sweet: instead of shoving a guy into the trunk of a car, he first politely asks him to get in himself, saying “head down, head down, thank you” as he closes the trunk. He begins a relationship with pretty paramedic Ally (Brooke Satchwell), but keeping his lives as a romantic boyfriend and kind father separate from his life as a violent criminal is, of course, complicated. Nothing drives TV plots quite like leading a double life.

At one point, Shoesmith defends his violent tendencies by declaring, “If I hit someone, I generally got a pretty good reason,” an echo of Cusack’s rationalization in Grosse Pointe Blank: “if I show up at your door, chances are you did something to bring me there.” But a couple of episodes earlier, Shoesmith brutally murders a man and is soon after told by the associate who ordered the hit that they went after the wrong guy. You always get the sense that these guys are kidding themselves that killing for money is somehow more morally defensible than a crime of passion.

An overwhelming number of the new fall shows I’ve watched in the last few weeks have dealt very directly with characters grieving loved ones—Kidding, Sorry For Your Loss, A Million Little Things are primarily about that, but it’s also a significant plot point of The First, Maniac, and Forever. And it can be a little jarring to go from one of those shows, where death is an earth-shaking event with emotional consequences, to a show like Mr Inbetween, where death is doled out swiftly and often depicted primarily as an inconvenience for the killer. Barry and Killing Eve dealt with the moral gray areas of their characters with more sensitivity, but all three shows have had to master a delicate balancing act, finding the humor in murder and violence without becoming coarsely unsentimental.

This week, FX picked up a second season of Mr Inbetween, and Barry and Killing Eve were both renewed months ago. So we’ll get a chance to see how all three of these shows maintain that balancing act beyond the initial premise. Any show about a killer has to eventually answer this question: Are their crimes going to catch up with them? Are they going to find some find of escape from the life they chose, and if they do, will they make some kind of sacrifice to redeem themselves? It’s not the kind of story that can be carried on for 10 years, but if they’re lucky they can get a good Breaking Bad-style five-season arc out of it. Barry’s Emmy win notwithstanding, none of the shows is a huge mainstream hit, which means they probably won’t give us a rash of copycat hitman comedies. But given the batting average of the movies that came out in the wake of Pulp Fiction, that’s probably a good thing.