“They don’t even know what they’re playing in here,” Polo G says excitedly, pointing out that G Herbo’s “Write Your Name” is streaming through the speakers of Harold’s Chicken. He pulls out his phone and raps a few bars for his Instagram Story, then says, “On gang, they playin’ real hits, you hear that?” It’s easily the most animated I’ve seen him all day.

We’re sitting in the back booth of the Los Angeles location of Harold’s, a well-known fried chicken chain from Polo G’s hometown of Chicago. The 22-year-old rapper, who recently relocated to LA and has already become a regular at this spot, sizes up which eight-piece wing tray has the most mild sauce, then explains what a profound impact G Herbo had on him growing up.

“Even though he’s from the city and probably isn’t even that much older than me, I used to listen to his shit all through my childhood,” he says. “I put a lot of my homies on to him, too, so even making music with him was a dope thing to me. I’m like, ‘Damn.’ In the city he’s a legend, and a lot of other places he’s considered a legend, because of all the shit he done did and all the messages he done brought. I was one of those people who was always tapping in when he was dropping shit, because he was really speaking to the type of shit I was going through.”

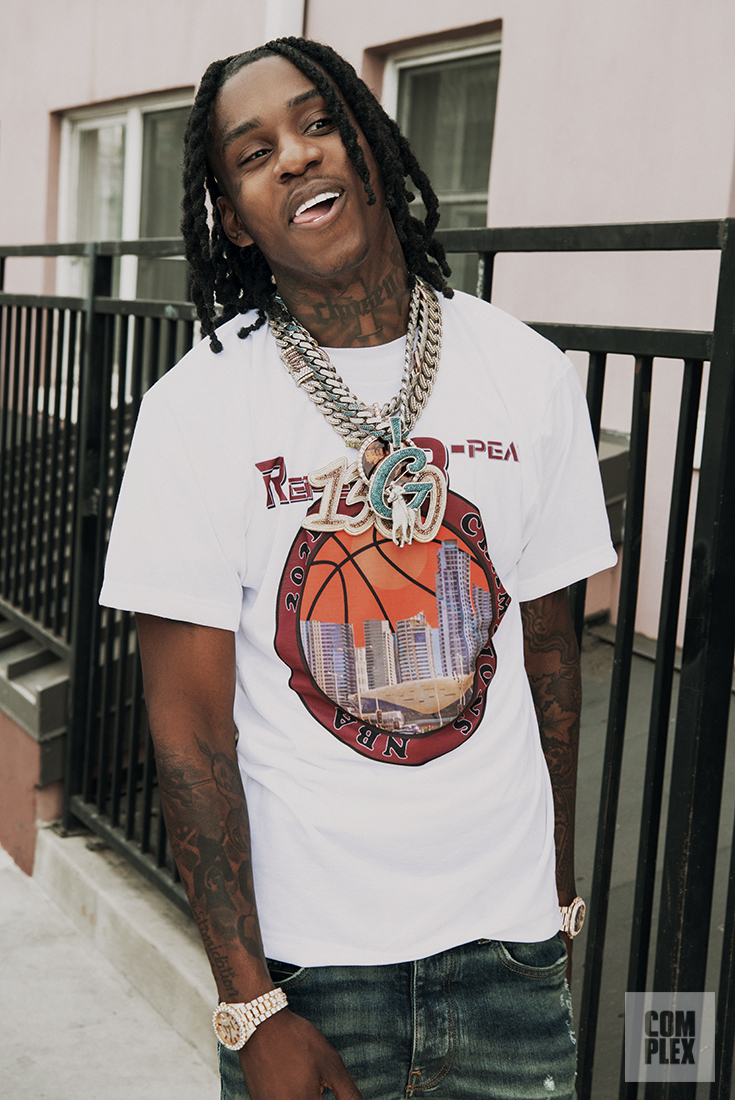

Now, it’s Polo G’s turn. The 22-year-old, born Taurus Tremani Bartlett in the Cabrini-Green neighborhood of northern Chicago, has come to the realization that his music can speak to the next generation, and it can help people push past their own struggles. His reach already exceeds that of Herbo, with his first album Die A Legend cracking the top 10 of the Billboard 200 chart and his follow-up The GOAT debuting at No. 2. Most recently, he earned his first No. 1 hit with “Rapstar,” which racked up over 50 million US streams in its first week. That’s the highest weekly sum for any male artist in 2021, and Polo is the only male solo artist to hold the No. 1 spot for two consecutive weeks this year.

Through his first two projects, Polo built on the thematic foundation that the city’s drill rappers of the early 2010s laid. But instead of the brutalist machismo and slurry, drowned-out AutoTune that some of his predecessors came onto the scene with, Polo opted for a clear-eyed look at the personal devastation that comes with growing up in communities affected by violence, over-policing, and governmental neglect. The silky melodies and dreamy piano that characterize most of his songs provide an accessible way into the music, but the real meat of it all is in the storytelling. On a song like Die A Legend standout “BST,” he’s able to uniquely position the tough choices that people from his neighborhood have to make in order to survive, rapping lines like, “Kid on the way, Mama’s bills late, gotta hustle hard, gotta get it/ Block was slow so he had to rob just to make ‘em smile on Christmas/ Caught a case, judge ain’t tryna hear all the things influenced my decisions.”

“I know I’m registering with people and helping them get through their shit,” Polo says, responding to a question about being able to influence young kids the same way that he was by someone like Herbo. “It’s a good feeling, because I get those messages, like, ‘Oh, you got me through a rough time.’ I really know how that be.”

The place Polo grew up in, Chicago’s Cabrini-Green housing projects, was first erected in the 1940s and ’50s, in the midst of a large migratory wave of Black families coming from the South. Former Chicago mayor Richard Daley, along with the city council, recognized a need for a significant increase in public housing that would be achieved in the form of large blocks of high-rise apartments. The Cabrini Extension—15 high-rise buildings known as the “Reds” because of the red brick exterior—was completed in 1958, followed by a few white towers known as the “Whites.”

These superblocks, in addition to being monolithic eyesores, were poorly maintained. The CHA was left to self-fund the projects as city finances fluctuated, forming dense pockets of impoverished residents in neglected infrastructure. After the riots following Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assasination in 1968, thousands of West Side residents were left without homes and the city dropped them into the Cabrini-Green projects without any support, leading to clashes between North and West Side gangs. Violence and drug use soared, racist policing tactics escalated, and funding dried up for maintenance. This all contributed to a general lawlessness in the area, and two police officers were sniped from one of the buildings in 1970. The whole project was recognized nationally as a striking example of the deteriorating state of public housing, and it became somewhat of a political boogeyman, before eventually being torn down over a period of 11 years from 2000 to 2011, as part of the CHA’s (also failed) “Plan For Transformation.”

Growing up in the “Reds,” Polo didn’t have it easy. The themes surrounding much of his music consider the on-the-ground realities of living in the conditions wrought by decades of urban blight and neglect. And in his songs, he isn’t afraid to touch on the experiences of surviving on public services, dealing with the desperation of everyone around him, and losing close friends at a young age, even though he’s a little more reticent about it in person. Throughout his catalog, he reflects on the coping mechanisms that a young kid has to develop to deal with it all, rapping bars like, “But my homies died young and that wasn’t part of the plan/ Flying on these planes, wish I could reach and touch your hand/ I don’t wanna be awake, that’s why I keep popping these Xans,” on “No Matter What.”

Polo has spoken at length about his addictions to Ecstasy and Xanax, almost losing his life to an overdose, and he’s had a few stints in juvenile detention centers for small-time weed possession and “soliciting unlawful business.” The cover art for his debut album displays the faces of nine people he was close with, whom he’s lost. And even though he lives in a cushy gated community in Calabasas now, far removed from it all physically, the cloud of violence never escapes him. After rescheduling our interview because of a last-minute trip to Chicago, Polo mentions very casually in conversation that he had to go see the headstone of a friend of his.

The sheer amount of talent coming out of Chicago in recent years is undeniable, with stars like Lil Durk collaborating alongside the Drakes of the world and appearing on Twitter “Rap Mount Rushmore” posts, while younger rappers like Polo are staking claim as up next (or up now, depending on how you look at it). But rising rappers have historically run into all sorts of problems in the city—either with police or the threat of violence in their own neighborhoods—and a lot of them ended up relocating to other centers of the music world. When I ask why so many rappers leave Chicago instead of trying to stay and uplift the communities from within, Polo says, “That’s just the culture of the city because of how bad it is. [There’s] so much shit going on [and a] high [murder rate]. They’re not gonna have to worry about that shit no more [if they leave Chicago]. If you come to a city where you ain’t got street beef, nobody is going to be mad to see you make it out.”

Chief Keef, who took the world by storm in the early days of the drill period, now resides in a mansion in Tarzana, California after essentially being forced out of the city by police (famously, his hologram concert was even shut down by Chicago police in 2015). Lil Durk currently lives in Atlanta, and Chicago’s Famous Dex and Polo G stay close to LA. Rappers who have remained in the city often continue to run into dangerous situations, as drill maestro Lil Reese was shot non-fatally in May for the second time in just 18 months. And Durk’s brother DThang, who regularly threw parties in Chicago, was senselessly murdered this month.

Polo considers it part of his mission to give back to the city, but he doesn’t foresee any quick end to the violence, retaliations, and long history of street beef stoked by years of built-up pressure. Gang activity is so closely associated with a lot of the music, with names of the deceased still being tossed around dismissively on wax, that building Chicago up to be a new hub for the music industry feels like a long way off to Polo. I ask what it would take to make Chicago a place where aspiring rappers want to come instead of leave, and Polo comments that it would be a very long process to get to that point. “You know how many n****s mad about their homies being dead?” he asks. “So if I touch 100 people, I’ve still got 10,000 left to go. That’s how hectic it is in Chicago. You gotta have a big enough microphone to reach the whole city to get that message across.”

Even though it feels like a monumental task, Polo is working to use his platform and resources to help lift up Chicago. When he visited his old elementary school and heard that they didn’t have a basketball team, he decided that he was going to create and sponsor an AAU team for the kids in his area. Now, the Chicago Grizzlies have started practicing again, post-worst-of-the-pandemic, and Polo is anxiously awaiting a time when he can stand on the sidelines, half cheering and half coaching.

Basketball and rap have always been the two pillars of Polo’s life (you can even find recent clips of him playing pickup with internet ball sensations like Tristan Jass on YouTube). Having grown up with basketball as an outlet, he understands what these types of activities can do for young kids in Chicago. “It just keeps them out of trouble. It’s like, if you ain’t got nothing else to do with your time all day, there’s nothing else to do but get in trouble,” he says calmly, as he looks up at Game 1 of the Celtics-Nets playoff series on a TV hanging over our heads. “[Evan] Fournier is getting sonned out there,” he adds. Later, he lights up at the mention of Derrick Rose, calling him “my all-time favorite player in the NBA.”

Polo’s goals are larger than just helping a single team or a few students, though. He wants to put new courts up all over Chicago and buy real estate around the Cabrini-Green area he grew up in, embodying Nipsey Hussle’s motto of “buying back the block.” Though somewhat soft-spoken, Polo sees himself as the type of figure who could have the impact of a Nipsey or a Tupac: rapping about social issues, while using his influence to lift up a whole city. “Shit, I want to give back to my neighborhood [and] Chicago in general,” he says.

Our conversation shifts to the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, and how to keep that momentum alive. Polo perks up a little and says, “The only way that that type of energy can live on is if it really registers in everyone’s brains that we’re fed up. Like, even right in the midst of protests, in the midst of the whole George Floyd shit happening, there was still police killing us.” He continues, “Police have to respect boundaries and learn to see things from a different point of view. We need something to police the police—some type of real penalty, because there’s a lot of officers that [murder people] and it gets swept under the rug. Then three years later, it comes out and their sentences ain’t nothing but like, three years. But if my Black ass goes and kills somebody, I’m getting 60 years, and I ain’t gon’ ever see the daylight.”

On the final track of his 2020 album, The GOAT, Polo takes an audacious rip at the same sample from Tupac’s “Changes,” rapping over the iconic beat about police killings and the systems that work against Black people in America:

“They just watchin’ us fail while they sittin’ back

The government cuttin’ checks, but can’t cut a n***a some slack

It’s hard to get a job, so we hustle and flip a pack

It’s all a setup, no wonder why they call this bitch a trap

Life was messed up, a matter of time till that n***a snap

Post-traumatic stress, so them triggers keep gettin’ tapped

R.I.P. Malcolm, I promise to conquer and fill them gaps”

Even though he seems a little reserved in person, Polo G is certainly not a shy guy. He comes across as steely and confident, making sure to clarify that even though the title for The GOAT was inspired by his horoscope sign—he’s a Capricorn, just like LeBron and Muhammad Ali, he proudly points out—he understood the other meaning of the name, happily opening himself up to the comparisons. After all, it is his goal to be one of the greatest.

As Polo gets ready to release his third album, Hall of Fame, he reflects on his long-term vision, explaining, “My motivation is knowing that I always want more for myself, and that there’s always a level up to keep improving. I know that I definitely ain’t reached my ceiling yet, and I know that I’ve got room for improvement on a lot of shit. So I just stay locked in knowing that, and knowing where I want to be 10 years from now: tapped into fashion, and looked at as one of the big names in fashion and an even bigger name in music. Ten times bigger and better as an artist than where I am now.”

As his career progresses, Polo is eager to learn more about different cultures and history, too. He says he wants to open his mind to new ways of thinking about the world, noting, “Even learning about your own history, it gives you more confidence to be who you are.” Reflecting on a recent trip, he adds, “Just looking at the history in Egypt, seeing that shit, I would have never been able to think that I could come see this. Being around certain things [like that] opened my mind up to knowing there’s more to the world.”

Polo is still processing his place in the universe—really just at the start of his own journey. The fame and everything that’s come with it has happened quickly over the course of just two years, half of which was during a global pandemic, so he hasn’t fully seen the fruits of his stardom yet. But even the slice of fame he has experienced has helped him come out of his shell a bit, and he wants to keep growing in that sense.

“[Before the fame] I wouldn’t say shit to nobody—not to a rapper, not to nobody—but then the more and more I’ve done this shit, I’ve been, like, ‘Fuck it.’ Because being in the corner and not saying shit ain’t gon’ get me nowhere. It ain’t gon’ bring me to the progression that I’m trying to see.”

Now that he has his 2-year-old son living with him and is on the precipice of superstardom, his priorities are a little different than they used to be. “Yeah, of course they’ve changed,” he says. “I’ve stopped doing a lot of shit, just anything involving negativity.” And now that rap is a full-time job, he admits that it can get stressful always having to be somewhere, so he values his down time a lot more than he used to. But he says, “I can still find my love for rap because this was a passion for me before I made it out. This was something I really used to get through rough times, but sometimes because it’s so work-heavy, I forget that. Then I’ll make a really hard ass song, or I’ll listen to my music when I’m going through something that really takes me back to, like, ‘That’s what this is supposed to be about.’ Just having fun and getting through tough times.”

With Hall of Fame set for release on June 11, Polo and his team at Columbia Records are still working through the final tweaks at the time we meet up, deciding which tracks will be on the deluxe edition, and sorting out a few final mastering and clearing issues. “I’ve been recording for a year-plus now, like I started it damn near before my last album dropped,” he says. Polo calls his first two albums his “coming out party,” but positions this one as a testament to his evolution into a more versatile artist. “My mentality was to kill—nah, it’s always to kill—but my mentality was to show that I’m evolving as an artist, trying new things, not being afraid to use different beats or try different flows, and just stepping outside the box a little more than I did last time.” Though his previous albums were sparse on features because, as he puts it, “I just wanted to show how good I can do it on my own,” this one will be jam-packed with stars like Young Thug, Lil Wayne, Nicki Minaj, DaBaby, Roddy Ricch, G Herbo, Pop Smoke, and more.

Polo doesn’t adjust his style to fit into new boxes on Hall of Fame, as much as he plays around the edges of those boxes so they better suit him. He’s not trying to sound like Fivio Foreign on “Clueless,” but he still sounds very at home over a more minimal Brooklyn-style drill beat next to Fivio and Pop Smoke. He takes a similar approach next to Nicki Minaj over a tropical CashMoneyAp beat with steel drums on “For the Love of New York,” and while singing tenderly about intimate moments of eye contact with his girl over soothing SephGotTheWaves guitar loops on “So Real.” But the moments where Polo shines brightest on the album are when he dives deeper into his storytelling roots and gives us the kind of from-the-ground commentary that he’s perfected, especially on the bookends of the album, “Painting Pictures,” and “Bloody Canvas.”

Looking to the future, Polo says he’s in the studio “all day every day” and reveals that the next step in his evolution is to learn to mix, master, and engineer all of his own music so he can get it to the place he envisions it in his head. He also wants to learn how to play instruments and “become more musically inclined.” He says, “I’m going to be a different animal after [I lock in to learn all of that] this summer.”

Having recently been shouted out by some in the more traditionally lyrical space, like Dreamville’s founder Ibrahim, Polo says he’s interested in trying those styles and working with people like J. Cole or Kendrick Lamar in the future, but wants “to get a little bit better lyrically in that style before I would jump on that type of song.” He adds, “But I feel like I definitely got it in me.” Polo calls himself a “perfectionist,” and says that he always “wants to be the best at whatever I try.” Based on the radio freestyle he spit on Power 106’s LA Leakers over DMX’s “Ruff Ryders’ Anthem” this past weekend, he certainly isn’t far off. And when I ask if anyone from that side of rap has reached out behind the scenes, Polo reveals, “My A&R was tapped in with Timbaland, so she sent him one of my songs and he was like, ‘Man that’s crazy.’”

As we finish our meal, Polo is buzzing at the thought of Hall of Fame coming out so soon, becoming visibly hyped up with his friend Tony while talking about how hard the likely deluxe cuts are. And even though it has the feel of a major label album meant for streaming success (which it is) that doesn’t take anything away from all the moments his talent for imagery and his natural charisma shine through.

His face brightens a bit when I bring up his latest single and video, “Gang Gang,” which features Lil Wayne. It was a moment of realization for him, where it clicked how far he’d come “since them red buildings,” as he put it on his breakout hit, “Finer Things.”

“When we were done with the video and everything, I was just sitting there thinking, like, ‘Damn, I really just shot a video with Lil Wayne,’” he says. “Wayne is like a master for like, 20 years. That’s the type of moment that will make you really realize how far you’ve come.”

Throughout our meal, there are several moments when fans try to do subtle walkbys with their phones out. Polo pretends not to notice, but you can tell he secretly enjoys it, as he flashes a sly grin whenever it happens. And when we step out into the sweltering heat of Hollywood Boulevard, there’s a group of onlookers and people waiting in line to get into Harold’s start pointing at Polo. Some of them whisper to each other, “Do you know who that is?” As Polo makes his way to a black car that’s waiting for him on the street, a group of women approach him and ask for photos, which again, he seems to delight in. While this is going on, a guy walks up to Tony and hands him a bag of weed. “It’s my own brand,” he says. Tony gives me a nug for the road (it’s bad weed).

Earlier in the day, Polo had mentioned that he loves to hang out in Hollywood, joking, “I told you it’s the trenches,” when his label rep told a story about two shirtless men who stopped traffic to fight in the street before he arrived. And as he finishes a mini photo shoot with a group of supporters, it seems obvious why he likes hanging in Hollywood.

He pauses for a second after slipping into the passenger seat, basking in the adoration of the fans gathered around his car. Then he shuts the door and zips off to Calabasas, where the responsibilities of fatherhood, and now superstardom, await him.